1.5 The Areíto Ceremony

Areítos constitute the fundamental and collective artistic expression of Cuban aboriginal culture, a fact that we have been able to perceive through the narratives and testimonies of the chroniclers of the time, who grant them a prominent place within it.

The word “areíto” is an Antillean word originating from the Araucanian word “Aerin,” meaning simply “to rehearse and recite.” It exhibits a deep musical meaning, characteristic of all popular and collective expression; that is, it was sung and danced collectively for a long time.

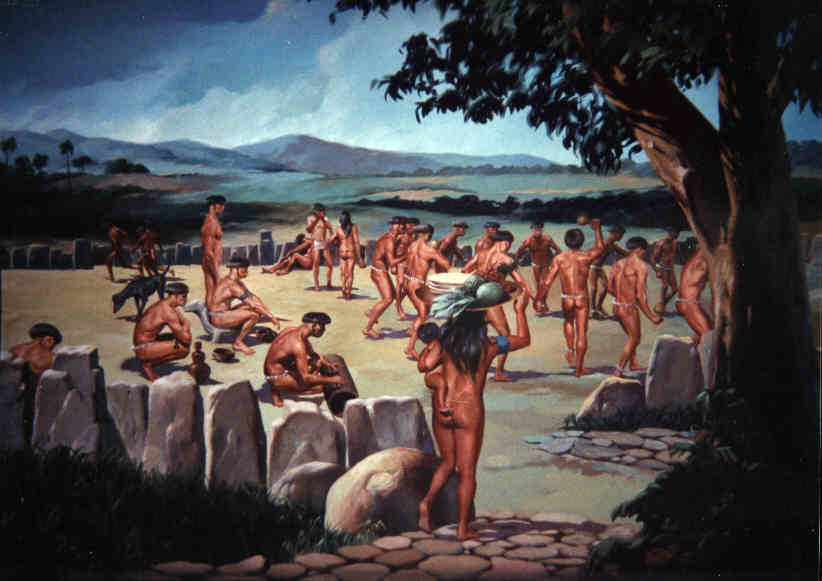

This complex manifestation of Cuban aboriginal culture fused song, dance, poetry, choreography, music, makeup, dance, rituals, and mime. Its characteristics include a dialogical structure in the song, with a couplet and a chorus; the dances were mimetic and had a ritualistic character.

The Tequina or coreuta (in an indigenous language), synonymous with master, artisan, or expert, a professional in a word, was the soloist or guide of the magical-religious ceremony, whose function was to initiate the singing and lead the choir. In them, we can see the first Cuban poets, musicians, and actors.

The themes represented in this choreographic and community-building performance were historical narratives that recounted the vital events and exploits of chieftains, as well as daily life events related to fertility and other issues.

The areíto had a social function of economic significance, as it was a way to gather individual strength for a collective work enterprise; this could be planting, building a house, a batey, a canoe, or the performance of a great sacred-magical ceremony to ensure harvests or rainfall, as well as to ward off natural disasters such as hurricanes and others. It also provided an opportunity to establish and strengthen relationships among members of the tribe, among foreign or neighboring tribes, and between the authorities and those governed.

Unlike in Mexico, Guatemala, Cholula, Yucatán, and other nations where there were sites designated for such ceremonies, the areitos lacked a venue or theater, platforms, amphitheaters, or appropriate sites for their performance; although there are references in Las Casas’ narratives in which he speaks of a place such as the plaza, batey, or caney.

The representation and imitation of collective work could be observed in them. The dancers’ makeup, made of feathers and flowers, and their bodies painted red and black. The men were more adorned than the women, who participated naked and without makeup if they were maidens; married women wore only petticoats. Masks were scarce, so we can say that they had not yet acquired the theatrical level of the incarnation of the character as a creation of the performer.

The areíto was the most purified manifestation of Cuban aboriginal politics, culture, and philosophies, the representation of the political and cultural organization of the first Cuban settlers.

Bibliography: Rine Leal. A Brief History of Cuban Theater.