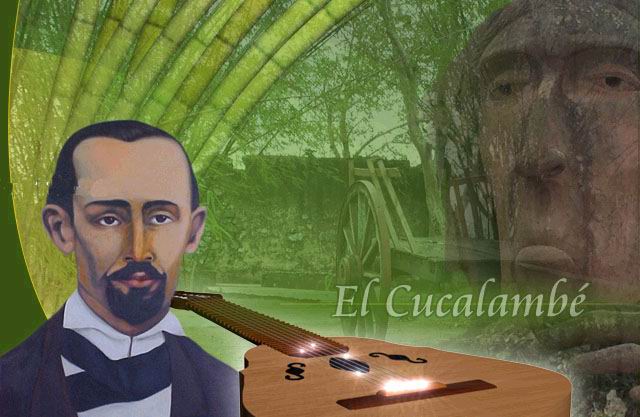

2.1.14.2 Juan Cristóbal Nápoles Fajardo, the Cucalambé (1829 – 1862)

Cucalambé’s life was marked by his belonging to the people, to whom he paid tribute and dedicated the offering of his verses. In his time, he was considered an epigone of José Fornaris, although in historiography and literary creation itself, Fornaris’s voice has had virtually no resonance, and his work, on the other hand, constitutes a living blood that still fertilizes popular poetry, firmly inscribed in the spiritual seed of Cuban lyric poetry.

Roberto Manzano refers to Cucalambé: “Poet of Tierra Adentro, Juan Cristóbal Nápoles Fajardo is the voice of the peasant who constituted us fundamentally as a people and the critical spirit of the citizen who yearns for a better life (…) He entered into nativism as someone who was waiting for a voice to unbridle his soul in a way that no one could surpass: his work is the supreme representation of the guajiro, and if there has ever been among us an aesthetic utopia that exerted an effective influence on its readers, to the point where it is not clearly discernible in what it refracted or modeled them, it was his so-called Cuban songs, which passed naturally and promptly from his lips to the heart of the people.”

However, the impact of his work was not so immediate, although it remained profound and sustained over the years. In 1857, he published his collection of poems, “Rumores del Hórmigo,” also conceived as a tribute to José Fornaris and nativist poetry itself. It did not achieve the popularity that Fornaris’s works had enjoyed, despite its superior artistic flair.

Cucalambé’s work is marked by a stylistic approach adapted to the simplicity of verse, where several dualities converge. One of these is the effective, unbroken symbiosis of the popular and the cultured in a refined but not artificial expression. The interweaving of Siboneyist and Criollist currents in his poetry has already been noted, while he delves into rural culture with verisimilitude, while incorporating a healthy dose of utopia.

His particular worldview also brings together elements of the two Romantic generations, a movement to which he openly subscribed and which he expressed in his metapoetics:

“Do you think, sincere friend,

You judge, candid friend,

That I studied poetics

To cry like Heraclitus?

No, not in my day! A fool

I want to be rather, or a bird

To the sound of my rough zither,

That he boasts Pindaric numen.

“Let them cultivate that genre

Those who are classic like you,

Not me, who lives with pretensions

And romantic touches.”

Cucalambé did not inspire later poets in the cultured world, but his legacy remained with the people, and there he did have followers who developed his expressive lines without strictly adhering to them. Among his contributions, the most significant is the definitive Cubanization of the décima, adapting it as an aesthetic container to the content of Cuban identity, moving beyond purely insular linguistic expressions—if one can speak of purity in literature, especially in the Cuban context.

One of his emblematic poems, Hatuey and Guarina, delves into the love between these two figures but also claims the absolute legitimacy of the Aboriginal resistance to the conquest, while suggesting an implicit call to begin the fight again: “Oh Guarina! War, war / Against that perverse race / That today threatens to set fire / My fertile and virgin land.”

Cucalambé’s poetry, steeped in the nativist movement, delves into the spiritual roots of the Cuban nation, the aboriginal culture uncontaminated by Westernism in the pre-Hispanic era, and from there points toward the suppression of Spanish influences at independence and a potential return to the origins. Much speculation has arisen regarding his disappearance and death, but the evidence suggests he was murdered for political reasons.

Without going into the existentialist zone of his poetry, we can conclude with these verses that suggest the poet’s symbolic firmness in the face of destiny:

“Oh world! Widespread sea

Where there are so many who sail

And indifferently they deny it

Protection of the helpless.

He continues raging,

Drags a thousand banners,

That I admire you alone

With extreme enthusiasm

I throw myself at you and I am not afraid

“Wrap me with your waves”