2.1.14 The cultivation of nativist poetry in the 19th century: criollismo and siboneísmo

Nativist poetry, which captured the uniquely Cuban in the realm of nature and the spiritual representation of the island and its inhabitants, had always accompanied expressions of popular lyricism; but later it would also be incorporated into more cultured poetic creation. Initial nativism, although a laudable approach to “the island,” carried with it a certain imported exoticism, inscribed in the Romantic movement, which did not yet penetrate the core of our identity, an amalgamation of the individualities and communities that populated our territory. It prioritized an idealized vision of peasant life and indigenous traditions, although this coexisted with costumbrist realism in its approach to its inner workings.

Roberto Manzano, in a recently published work that recovers and celebrates the national lyrical tradition, refers to the gestation of this poetic trend: “The diversion inherent to lyrical poetry, always so saturated with a playful character; the old clichés of escape from the hustle and bustle of the world, of the calm and beneficial peace of nature, of the superiority of the wild, of the sacred connection to a lineage; the aspiration to congeal a popular expression, which had already begun with happy results; the joy implied in the act of founding, with which all poetry of that time was imbued; the presence in each area of indigenous traces and the peculiarities of the peasant who had inherited them, which brought two emblematic figures to the lyrical table: the cacique and the guajiro; the need to outline what was implicit in the recent tradition, which supported the existence of three symbolic axes for the pantheon of the new imaginary: the “woman, the homeland, God, and that an atmosphere of lively propagation covered these spheres: freedom; all these elements welded together, in the eager unity of embodiment, and in the electrical contacts of the most lucid and energetic consciences working to build a nation, produced the poetry of criollismo and siboneísmo, that is, of our nativism as a constituted school, which crystallized what was to come and would survive in multiple ways.”

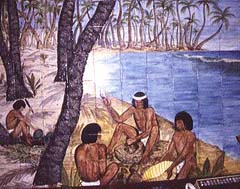

These movements were inextricably linked to nature and a freedom of movement within it that already contained yearnings for political freedom. Criollismo, which preceded Siboneyismo, addresses country life and the guajiro as the protagonist of the rural space, with their customs and values, but transformed by the urban and cultured perspective. Siboneísmo, or Siboneyismo, as other scholars call this movement, attempts to rescue aboriginal traditions and incorporates many of their linguistic expressions, diluted in the communities by the effects of centuries, coupled with the atrocious process of colonization.

Although these two currents can be abstracted in research, in poetic practice both lines were closely intertwined. Criollismo already inherited the entire tradition of the popular décima, widely disseminated among the popular strata of the colony, and the oral tradition of peasant improvisation, which enlivened rural festivals and recreational activities. Furthermore, the repositories of the remnants of aboriginal culture were precisely the peasant communities, so both trends have a common origin and would ultimately flow toward the same poetic purpose.

With these currents, poetry delves deeper into the inverse spiral of the search for Cuban identity, not only through the landscape but also in its approach to the face and idiosyncrasies of the people who populated the island, or had lived there in the case of the aborigines, whose anonymous faces were already part of the spiritual foundation of the nation. Nativist poetry is criticized for having ignored the Black people, slavery, the misfortune and collective greatness of this vast human group; however, these extra-literary considerations fail to take into account that no human expression can completely escape the siege of its time and the dominant social consciousness.

These styles had both regular and more occasional practitioners, such as José Jacinto Milanés and Plácido; José Fornaris, for his part, devoted himself entirely to this expression; however, it wasn’t until the mature work of Juan Cristobal Nápoles Fajardo, Cucalambé, that the two expressions merged and entered the realm of cultured lyric poetry with complete authenticity.