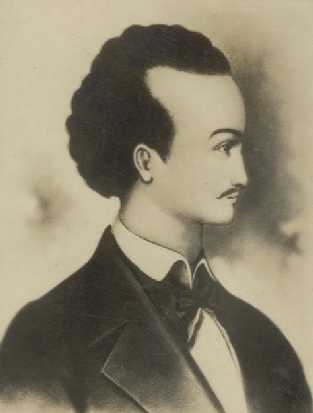

2.1.6 Gabriel de la Concepción Valdés (Plácido), poet and alleged conspirator, foundling since 1809

Gabriel de la Concepción Valdés, better known by his pseudonym Plácido, was born in the early 19th century. The exact date is unknown, only that he was placed in the Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad in Havana on April 6, 1809. His baptismal certificate describes him as “apparently white.” However, his racial origins sparked controversy throughout his short life in the cultural circles in which he moved. He was executed by firing squad on June 28, 1844, for alleged links to the so-called “Ladder Conspiracy.”

His dual status as an illegitimate child and a mixed-race man brought him all the prejudices inherent in nineteenth-century society, yet he exerted a certain fascination on his contemporaries, even more so given the real facts and the fabrications woven around his death. His works were published and widely distributed throughout the country, with repercussions that would reach even the mother country. This is one of the cases in which the influence of the author’s personality is as powerful, if not more so, than his work in explaining his success and the interest he arouses in posterity.

In this sense, the Doctor in Philological Sciences, Daysi Cué Fernández, has expressed: “Artisan and foundling, and apparently mulatto, thanks to his talent he managed to occupy a prominent place in Cuban literature, but this did not save him from physical and moral annihilation (…) Aside from the melodramatic overtones in which his life cycle appears wrapped, the truth is that from his enigmatic birth until his execution in his youth, accused of being the ringleader of a conspiracy of blacks, his existence developed through unusual channels and this has contributed greatly to his notoriety.”

Plácido is considered a bard of early Romanticism, although this movement was primarily expressed in formal aspects, and it seems that the poet did not experience the tremors or intimately share the tragic vision of life associated with the Romantic worldview. Poetry constituted a means of livelihood for him, partly for psychological survival but above all from an economic point of view. He even signed contracts in which he received a tiny sum for “providing” a poem daily to a certain publication. His status as a poet allowed him indirect access to high society circles, without, however, actually appearing in them.

His “poetic exercises” ranged from a rather naive neoclassicism to truly romantic forms. He possessed a natural talent for versification, but lacked a thorough education, and his literary formation was determined by the chance of his readings and personal contacts. He composed some laudatory poems dedicated to monarchical figures, constantly inserting recurring references to “the homeland” and “freedom” between his verses, revealing his innermost aspirations. These appear to be true, even though the label of conspirator that cost him his life was unjust, and he even revealed weaknesses or made some false confessions during the trial leading up to his conviction.

His best-known poem, “Prayer to God,” was claimed to have been recited by the poet on his final walk to the scaffold:

“Being of immense goodness, mighty God!

I come to you in my vehement pain;

Extend your almighty arm,

Tear the hateful veil of slander,

And tear off this ignominious seal

With what the world wants to stain my forehead!

(…)

But if it suits your supreme omnipotence

May I perish like a wicked and impious person,

And that men my cold corpse

They insult with malignant complacency,

Let your voice sound, and my existence end…

“Thy will be done to me, my God!”

The poem is vibrant in its rhythmic conception and thus has a profound effect on its listeners; however, Plácido had become so accustomed to merely external verse forms that he struggles to convey the true pain that grips him in this final stretch of his life. In this case, we can apply Fernando Pessoa’s well-known verses: “The poet is a pretender / he pretends so completely / that the pain he truly feels seems feigned.” Despite the lack of support for the accusation of conspiracy, the desire for independence is latent in the different facets of his work, which dates back to the dawn of nationality, and the myth associated with it and his life has survived to this day.