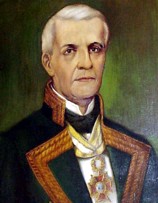

2.3.5.1 The Fatalist, by Esteban Pichardo Tapia (1799 – 1879)

Esteban Pichardo was a prominent geographer of his time. He traveled to various Cuban cities and dedicated himself to creating maps and other cartographic documents. He received numerous awards for his scientific work. He is also credited with a volume of poetry and the extensive novel “El fatalista,” published in 1866.

The novel reveals a costumbrist intention from its very preamble: “Several customs and other local circumstances are indicated, focusing specifically on the capitals of the departments of Havana, Puerto Príncipe, Santiago de Cuba and some other places, so that they will be more interesting to those who know these regions well; it being understood that as much care has been taken to avoid anachronisms as to avoid implausibilities and Milesian Fables.”

Later, he adds as his purpose: “To paint our world as it is; to anatomize the Cuban social body in all its members, from one Department or another, easily seeking the possible corrective in defects; to isolate in an individual dubious ideas of predestination; this is not to slander, nor to establish axioms of belief.”

He undoubtedly successfully captured Cuba’s geographical nature in his scientific works; however, as for social reality, the text seems jumbled, and stories follow one another without a complete logical connection. The author states that many of the narratives have a real-life setting, compiled during his excursions into the interior of the country; however, the interplay with reality culminates in a social portrait that doesn’t entirely resemble its reference. The practices he refers to, although perhaps existing, are not representative, and therefore this portrayal of customs fails to reach society as a whole.

The intention to shock the reader can be captured in the text through the exoticism of some of the landscapes and the painterly brushstrokes used to describe the Cuban countryside. The language becomes so particularized that it hinders communication and closes off public spaces. The passages with sexual content, including explicit references to rape, are somewhat surprising, uncommon in the literature of the period.

Cubanness is here restricted to these mere colorings of life in cities and rural towns, without political connotations at a time when most intellectuals were taking a stand on this matter and the country was already becoming a hotbed of conspiracy.

The idea of predestination, which could be considered deterministic were it not for the lack of correlation between preconceptions and realities that mysteriously coincide, is constantly reiterated throughout the text and weakens the element, in addition to the reader being able to foresee the outcomes.

Perhaps this text is symptomatic in that it shifts our focus from the relevant events that were truly unfolding in the nation to externalist manifestations of Cuban identity. However, in its description of environments and landscapes, it does manage to reflect some fragments of the complex network of nationality.