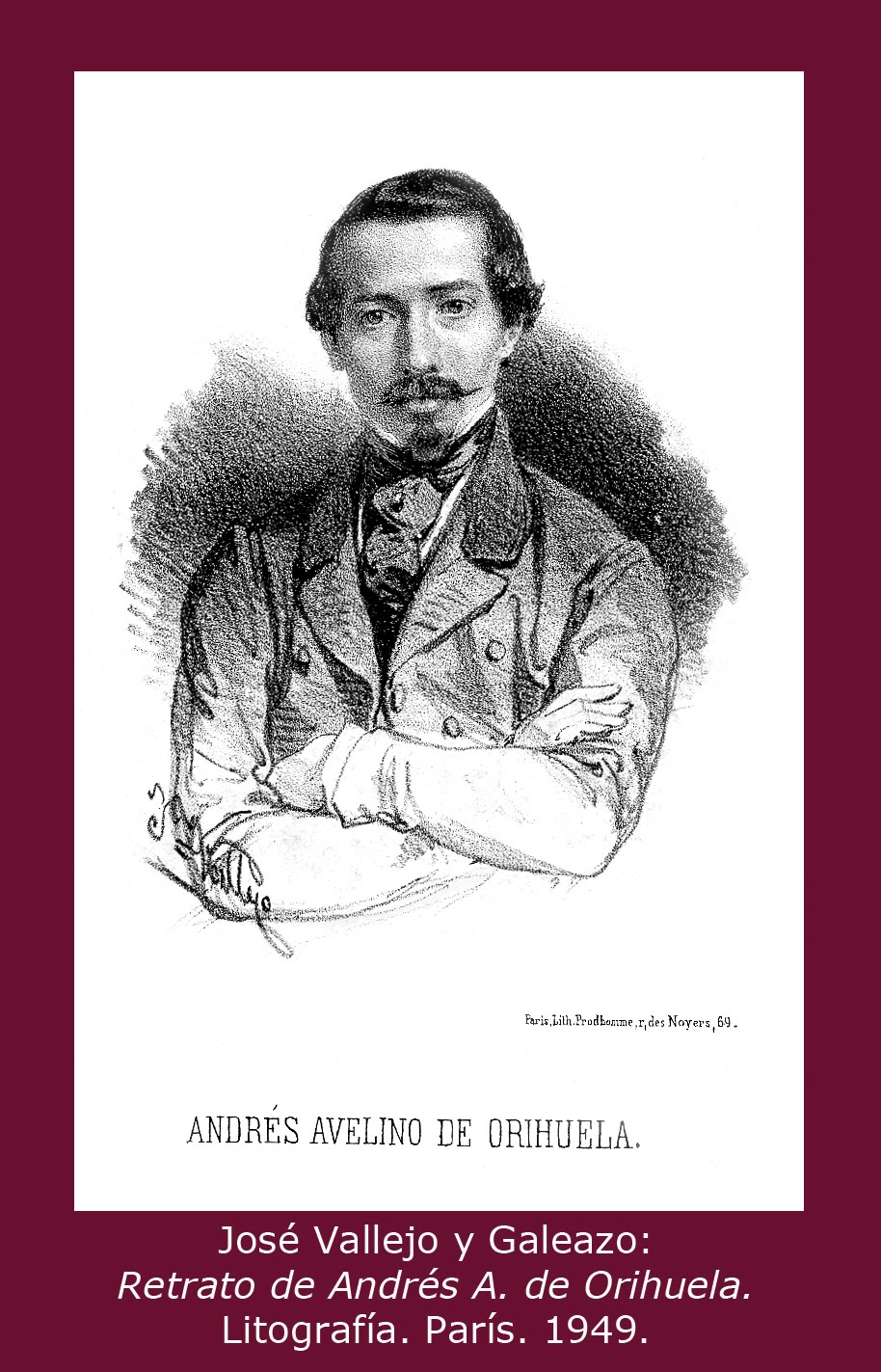

2.3.5.3 The sun of Jesús del Monte, work of Andrés Avelino de Orihuela (1818 – 1872)

Although the writer was born and died in Spain, he lived part of his life in Cuba, finding inspiration in its locations and inhabitants. He contributed to the publication of “The Romantic Garden” and even founded the humorous publication “El quitapesares.” He belonged to the Economic Society of Friends of the Country.

A first reading of the text, which some critics have focused on, reveals romantic elements in the style of melodramatic serials, without achieving the artistic fabric of other productions of the period; but it does exhibit “stitches” that give it significance for Cuban literature and even for the exegesis of the social fabric in which he lived, to which he perhaps applied a perspective less contaminated by the very consubstantiality of the social terrain, the tellurism characteristic of writers born in Cuba.

The chapter that revolves around the execution of the poet Plácido, which took place in 1844, stands out. In this sense, from a historical perspective, Daisy Cué Fernández points out about the work:

“An artistic work cannot be expected to have the precision that history lacked; however, the tendency to place the poet on the same level as the martyrs of Christianity reduces the possibility of capturing the internal contradictions of this man struggling against an adverse destiny. The characterization, too flat, contributes nothing to the development of the conflict, although in its time this work must have had a subversive yet progressive character, insofar as it denounces the racial prejudices and excesses committed in the year of the leather.”

Although it is true that it denounces the scourge of slavery, the work is more in line with the costumbrista line in terms of the description of the lives of slaves, from elements not only related to the exploitation they suffered, but also the entire cultural universe that the institution of slavery had not been able to obliterate, its music, traditions and religiosity, which survived and were nourished precisely by oppression, as a symbolic means of escape.

From an ideo-thematic point of view, the work presents, with a certain camouflage of convention, theses of relief when analyzing the ideological context of the period, opposing the double standards of the law and the prevailing racial prejudices.

The author was an annexationist, but given the historical period and, above all, the fact that he was born in Spain, this demonstrates the extent to which he felt more Cuban than Spanish, also evident in a certain irony when he refers to elements and people that symbolize Spanish colonial rule.