2.3.6 The theme of slavery in Cuban literature, some significant works

In the first half of the 19th century, the Cuban sugar economy was based on the exploitation of slave labor. However, some sectors were already striving to replace slave labor with wage labor, and abolitionist tendencies emerged on the ideological level, but these were held back by fears of a revolution like the one that had taken place in Haiti. Those who already saw it as a moral wound nevertheless feared the remedy and took many half measures.

That some advocated manumission does not indicate the absence of racial and social prejudices, since the strict class division of society was not at all questioned. Rather, the most revolutionary conceived progress as development capitalized by the dominant economic sectors, namely the emerging bourgeoisie, to which the vast majority of intellectuals belonged or aspired to belong.

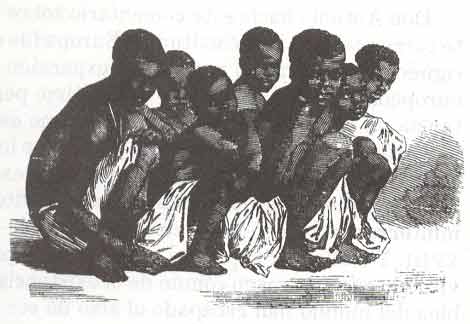

Siboneismo and criollismo, even with their ostentatious desire to represent the autochthony of Cubanness, despite their contributions, had blatantly ignored the Black roots of our culture; but they would not be completely silenced. Many authors addressed the topic, and their accounts of this period reveal a sincere identification with Black protagonists, especially those with the most romantic power. At this point, recognition of the heroism of the runaway slave has even been suggested; but this is debatable given that this was one of the types most feared by white society due to its rebelliousness and its unpredictable consequences.

Black characters were often presented as idealized and filtered through the axiology of whites, so deficient and contradictory in its essence, with the exception of the slave poet Juan Francisco Manzano, who would not have difficulty narrating the horrors he suffered “in his own flesh”, at the hands of the whip and the ferule.

However, while some stubbornly ignored slavery, others focused on the phenomenon and even grasped its inherent literary potential, as was the case of Félix M. Tanco, who wrote a letter to Domingo del Monte, containing very suggestive ideas: “There is no more poetry among us than the slaves: poetry that is spilling out everywhere, through fields and towns, and that only the inhuman and the stupid do not see; and warns that as the still very muzzled working class becomes civilized, albeit slowly, the slavery of blacks will rise in the same proportion as a deformed, mutilated, horrific, but poetic and beautiful shadow.”

One of the topics to which writers obsessively returned, both within the context of black themes and in so-called costumbrista literature, was that of racial contamination, the “original” sin of miscegenation; its roguish face reared its ugly head on every street corner in the city and in the pages of many narrative pieces. Those from this period, although they do not address the phenomenon of slavery in all its inhumanity and heartbreak, have the merit of opening a channel for society to reflect on itself, while also preceding later ethnic and anthropological studies of Cuban culture in its connection with black roots.