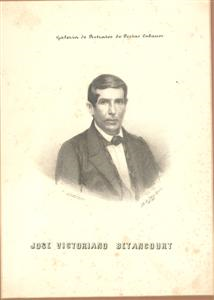

2.4.2 Costumbrismo in the articles of José Victoriano Betancourt (1813 – 1875) and his foray into poetry

José Victoriano Betancourt graduated from the San Carlos Seminary, attended the Domingo del Monte gatherings, and collaborated with José Antonio Saco in the founding of “La Siempreviva.” He achieved greater fame with the articles on customs and traditions he wrote for publications such as “El Almendares,” “Diario de la Habana,” and “Cuba Literaria,” among others, than with his poetry.

His style has sometimes been described as slovenly; however, in reality, this was a deliberate adoption by the author, so that the language would serve as a mere mirror, shining only on the realities he intended to capture. This lends a freshness to his descriptions, particularly through the use of popular vocabulary and the general colloquialism that runs through his texts. The marginalized and even marginalized sectors of society are addressed with a degree of casualness, although his critical gaze is also directed toward the highest levels of the social order.

His criticisms are framed within a reformist ideological conception that fails to discern a way to address the root of the evils he points out. His verbal depictions of customs largely capture general human types along with truly insular characters, brought to life in his texts in a way that anticipates realism.

His works were not included in any collection until 1941, with a foreword by Mario Sánchez Roig and Mario Cabrera Saqui. His most noteworthy texts were “The Usurer,” from 1848, in which he ventures ideas that may influence the identification of this character with the typical bourgeois, which would emerge as capitalism took hold on the island. In 1850, he published “The Blind Ticket Seller,” in which he typifies the character of a disabled person, at once an expression of the poorest social classes and therefore of the prevailing inequality.

In addition to this and other texts with a costumbrista imprint, the author wrote some verses in which he was not entirely fortunate in anchoring in popular taste, since he did not manage to singularize his thought or find his own expressive channel within the romantic current, even so some of his verses stand out for their musicality, and the stanzas cited below, belonging to his poem “Las ninfas y genios del Almendares” have a tone of “festive elegy” curious from the aesthetic point of view, although they lack sentimental depth:

“Goodbye, beautiful and vates

That you drink the clean waves

From the exalted Almendares,

How much my lyre sang!

Goodbye, the heavy hand

From the enraged fate

It takes me to my home,

Where I saw the light of day,

My chest is beating

Of sublime sympathy

From drunken love he will exhaust

Chalice of immense delights!

(…)

Children of song! Let them sound!

On the shore of the paternal river

To the power of feeling

Your harmonic lyres.

You, who are crowned

With the flowery garlands

With which they adorned your temples

The nymphs from Almendares!

Join me in my tears,

And your heartfelt song

Sweeten the bitter sorrow

That destroys my soul.

Goodbye, and heaven return me

To this beloved shore,

That I will greet joyfully

“Playing my sweet lyre!”