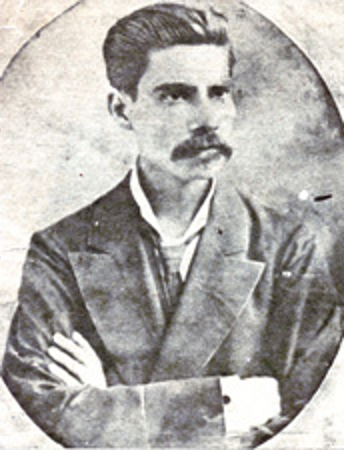

3.2.3.1 The journalism and oratory practiced by Esteban Borrero (1849 – 1906)

Esteban Borrero’s literary personality spilled over into various creative fields, among which journalism held a prominent place; albeit intermittently, since, according to Julián del Casal, he struggled to adapt to the precepts that generally governed editorial boards, especially due to his markedly individualistic way of thinking, which did not always fit with the current concepts of the subjects he covered.

The subjects he wrote about were diverse; he was naturally interested in medicine and everything related to education, both in terms of pedagogical theories and the need to promote public education. He always admitted Black children to his classrooms, both in Cuba and when he taught at the San Carlos Club school during his time as an exile in Key West, United States. This is a testament to his advanced social views. Politically, he was also radically pro-independence.

He was also interested in cultural and literary studies, not only in relation to Cuban topics and writers but also in the flow of world literature. This is the line in which he published a series of texts entitled “Around Don Quixote,” which he published in 1905.

His oratory, although not political in nature, according to those who heard him, possessed the captivating gift of absolute authenticity, which would have been highly effective as a proselytizing effort for the cause; however, it was never his nature to try to win followers, and his speeches always had a discourse-like tone, far removed from the purpose of convincing the masses; perhaps for this reason, he succeeded without intending to.

His oratorical style would earn him the admiration of many writers and intellectuals. Julián del Casal went so far as to say: “Of all the conversationalists I have heard speak in my lifetime, this is the one who has amazed me the most. Hearing him for the first time, I thought I was in the presence of Barbey d’Aurevilly or Villiers de L’Isle-Adam. This is how I imagined these geniuses must have spoken.” The words, as they came from Borrero’s lips, imitate the waves of a torrent. Sometimes they are serene, blue, luminous, reflecting the state of his mind, where ideas, like stars, take pleasure in shining. But instantly the wind blows, the sky blackens, and the waves of the torrent begin to boil. Then they leap, foaming and dark, over the riverbank, sweeping away the plants, destroying the dikes, and uprooting the trees, until the “A rainbow appears in space and makes it retreat from the furthest point that could be conceived and where it had arrived in its swift, sonorous and devastating course.”

For his part, Manuel de la Cruz, in his study published in 1892, “Cuban Chromites,” went so far as to state: “He has the abundant oratorical style, full of majesty and pomp, which is in the nature of our sonorous and noble speech, harmonizing the sobriety of an intelligence accustomed to the disciplines of the observational sciences, with the finery, arabesques and plumes of a provident, discreet imagination, which is always an opportune and exquisite assistant, never a slick, disheveled, party-pooper intruder.”

Esteban Borrero’s oratory and journalistic work complemented each other well in terms of his approach to the subjects he pursued, especially in regard to pedagogy, a topic on which he perhaps placed an unusual emphasis, considering it crucial to the country’s development. His texts were published in “El Colibrí”—which he founded—”El Oriente,” “El Triunfo,” “Revista Cubana,” “El Fígaro,” “La Habana Elegante,” and “Revista de Cuba,” among other scientific publications especially associated with his profession as a physician.

This section cannot be concluded without citing the opinion of his dear friend Enrique José Varona, whose content is perfectly applicable to the field of Borrero’s prose and poetic writing: “it was necessary to have lived in his company, to have managed to hear that word heated by the deepest feeling, to have some idea of how the human soul can bubble in the word and shine in the eyes.”