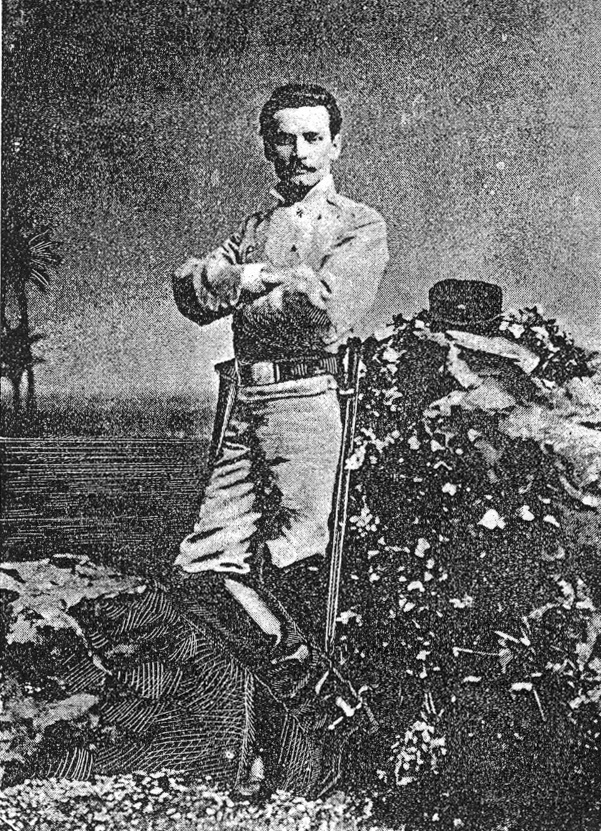

3.3.4 The career of Manuel Sanguily (1848 – 1925) as a political speaker

One of the earliest known oratorical pieces by Manuel Sanguily dates from the historic moment of the Guaimaro Assembly, although he had previously served as a speaker at the literary gatherings of the Havana Lyceum. Associated with the jungle, although from the perspective of law—a discipline he had begun studying at the university before the outbreak of the Ten Years’ War—was the role of defense attorney he often played in courts-martial.

He moved to Spain after the failure of the first independence struggle, where he completed his law studies and returned to Cuba. He became a prominent speaker at the Revista de Cuba evenings, the José María de Céspedes gatherings, and later at the Matanzas Liberal Youth Circle, where he delivered a speech entitled “Elements and Characteristics of Politics in Cuba,” the first of its kind he produced after the Zanjón War, which also included a profound tribute to the heroes of the Great War.

“The august shadow of some hero still rises in our conscience, who only lives the life of cowardly memory in whispered family confidences, indignantly waiting to emerge whole into the light in the noble and frank immortality of history (…) everywhere, in squares and streets, in the mountains and plains, one feels here, through the poetry of memory and the bitterness and sadness of reality, the immortal elements of the immortal religion of our spirit stir – like living and numerous atoms – the dispersed and sonorous notes of that sublime chorus of patriotism that resounds in the heart of our people… the only bell of legitimate glory for Cubans.”

Sanguily’s discourse eludes political clichés through a wealth of nuances and an evocative and lyrical approach that transcends the boundaries of mere persuasion. He moved with relative ease between the political and the academic, although he always included some pointed allusion, more or less incisive, to the political situation associated with Spanish colonialism.

Among the topics that served as leitmotifs of his speeches were the execution of medical students, as well as those pieces filled with a tone of summons to take up the struggle once again. From a more academic perspective, his lectures stand out: “Moral and Political Dualism,” “On José María Heredia,” “The Situation, Its Causes, and Its Remedies,” and “The Discovery of America,” delivered between 1888 and 1892.

After the outbreak of the Necessary War, he settled in New York and throughout the war period gave numerous speeches, including one in 1895, commemorating October 10. In it, he praised Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, precursor of the Ten Years’ War, and José Martí, as the unifying force that led to the beginning of the feat that was taking place at that time.

During the Republican period, he held several political and academic positions, including that of Secretary of State in the government of José Miguel Gómez, where he championed a defense of national sovereignty. He also held the chair of Rhetoric and Poetry at the Havana Institute, of which he was also director.