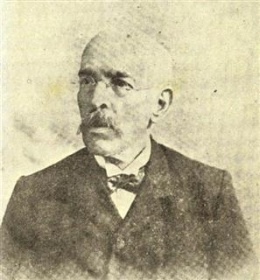

3.4.2 The political prose of Rafael María Merchán (1844 – 1905)

Rafael María Merchán was born in Matanzas. His father was of Colombian origin and would contribute to both countries through literary and patriotic influence. He worked as a typographer for the Manzanillo newspaper “El Eco” and also as a typesetter. In his youth, he was interested in a career in the Church but abandoned it after entering the Seminary of Santiago de Cuba. His vocation for literature was a constant throughout most of his life, encouraged from the moment he began working as a typographer.

He taught at the Santo Tomás School in Havana, and in this regard, he would defend the need to abolish corporal punishment and establish some precepts of Cuban pedagogical practices, all in newspaper articles. Journalism was not only a space for him to express his views on education, but above all a means of conveying his political ideas, of a markedly separatist nature that would cause him difficulties with the Spanish authorities.

In the early stages of his political work, he published articles in the newspapers “El Siglo,” “La Opinión,” and “El País.” In the latter, under the headline “Laboremus,” he published an article on November 15, 1868, inciting struggle against the colonial regime. This article used allegorical language and cultural references to evade censorship. He skillfully substituted “struggle” for work, effort, and sacrifice, giving the impression that he was referring to progress, not freedom, as an end. A brief excerpt is reproduced below:

“What we are certain of is that civilization is achieved only through hard work, self-denial, and sacrifice, and that human progress cannot be achieved without resigning ourselves to the trials of suffering. All those names that have been left floating after the shipwreck of past generations, to receive from posterity the gratitude denied them by their contemporaries, demonstrate only too clearly the evidence of this truth: There is no progress without fatigue, without struggle there is no victory… We cannot invite anyone except to a table of suffering, to which we must approach standing, with staff in hand, and wearing sandals like the chosen people celebrating Passover in the days of their pilgrimage toward the promised land. Will those who come to share the bitter leaven with us be numerous?”

From this text, the custom of calling those who fought for the island’s freedom “laborers” was acquired. Due to his journalistic and insurrectionary activities, he was forced into exile in the United States in 1869. There, he published an article entitled “The Cuban Revolution,” which denied that Cubans expected support from the United States instead of fighting with their own weapons.

After living in Colombia for a time, he returned to Cuba after the signing of the Pact of Zanjón and joined the autonomist forces; albeit for a temporary reason, always stating that he would join the struggle as soon as another insurrectionary movement broke out. At the beginning of the 1895 conflict, he wrote a series of articles that appeared in the Correo Nacional of Bogotá. These were later compiled in a book entitled “Cuba, Justification of its War of Independence,” which constituted a well-documented indictment of colonialism and a defense of the justness of the Cuban cause.