3.5.3 Testimonies from those deported to Fernando Poo in 1869

Fernando Poo was the name given at that time to the tropical volcanic island of Bioko, part of Equatorial Guinea. It served as the arbitrary destination for approximately 250 people deported by the Spanish colonial administration. Some had refused to emigrate, and others lacked the resources to undertake the attempt, and were actually or allegedly linked to the conspiracy movement developing in cities not at war.

In 1869, two works were published in New York recounting these events, still little known today. The first text is by Miguel Bravo Senties, entitled “Deportation to Fernando Poo. Account given by one of the deportees.” The other text, “Those confined to Fernando Poo, and impressions of a trip to Guinea,” was written by Francisco Javier Balmaseda (1823–1907), who already had a career as a poet, playwright, and journalist in his native Remedios.

Francisco Javier Balmaseda’s text is superior from a literary point of view. Both seek to denounce the precarious living situation they endured during confinement on the island, supported by a series of historical documents that were generated around the deportation and, above all, the detailed account of what was happening as they approached their destination and settled permanently in the territory.

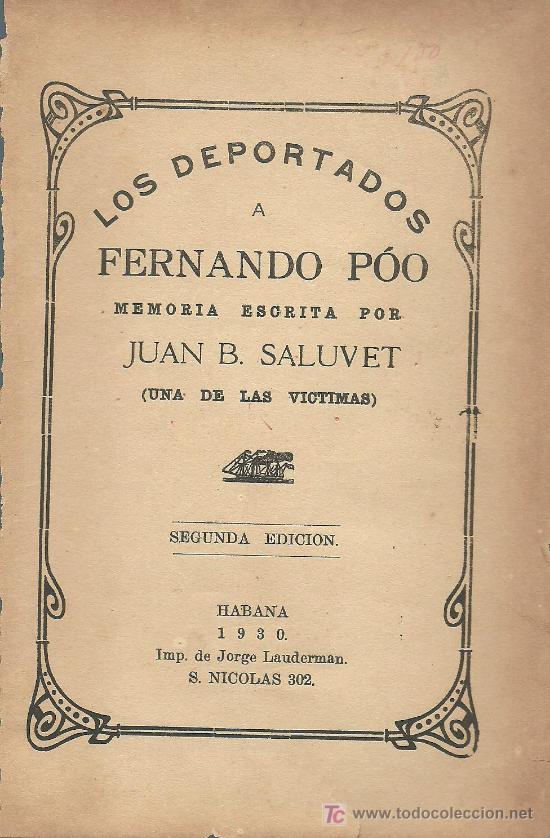

Already with some temporal distance from the events of the deportation, between 1892 and 1893 – symptomatic of the fact that so many years had passed and that a new rebellion was imminent, already sensed – the topic arose again in literature, this time with the text by Juan B. Saluvet, “The Deportees to Fernando Poo in 1869”, in which there is hardly any hint of denunciation but rather the poorly concealed objective of integrity.

For his part, the cigar maker Hipólito Sifredo y Llópiz, who supported the autonomist party, published “The Cuban Martyrs in 1869.” Although he recounts his experiences and failed desire to return to Cuba with a high degree of veracity, the text does not convey any ideological purpose in itself, but merely records the trials and tribulations of the years of deportation.

All these texts, of unequal literary quality, nevertheless illustrate the Spanish arbitrariness that initiated the complex “adventure” and constitute testimonies of little-known events, perhaps due to the whirlwind of actual war actions and the accumulation of campaign literature texts, which allow us to reconstruct colonial history and figure in the historical-literary framework of the dawn of the nation.