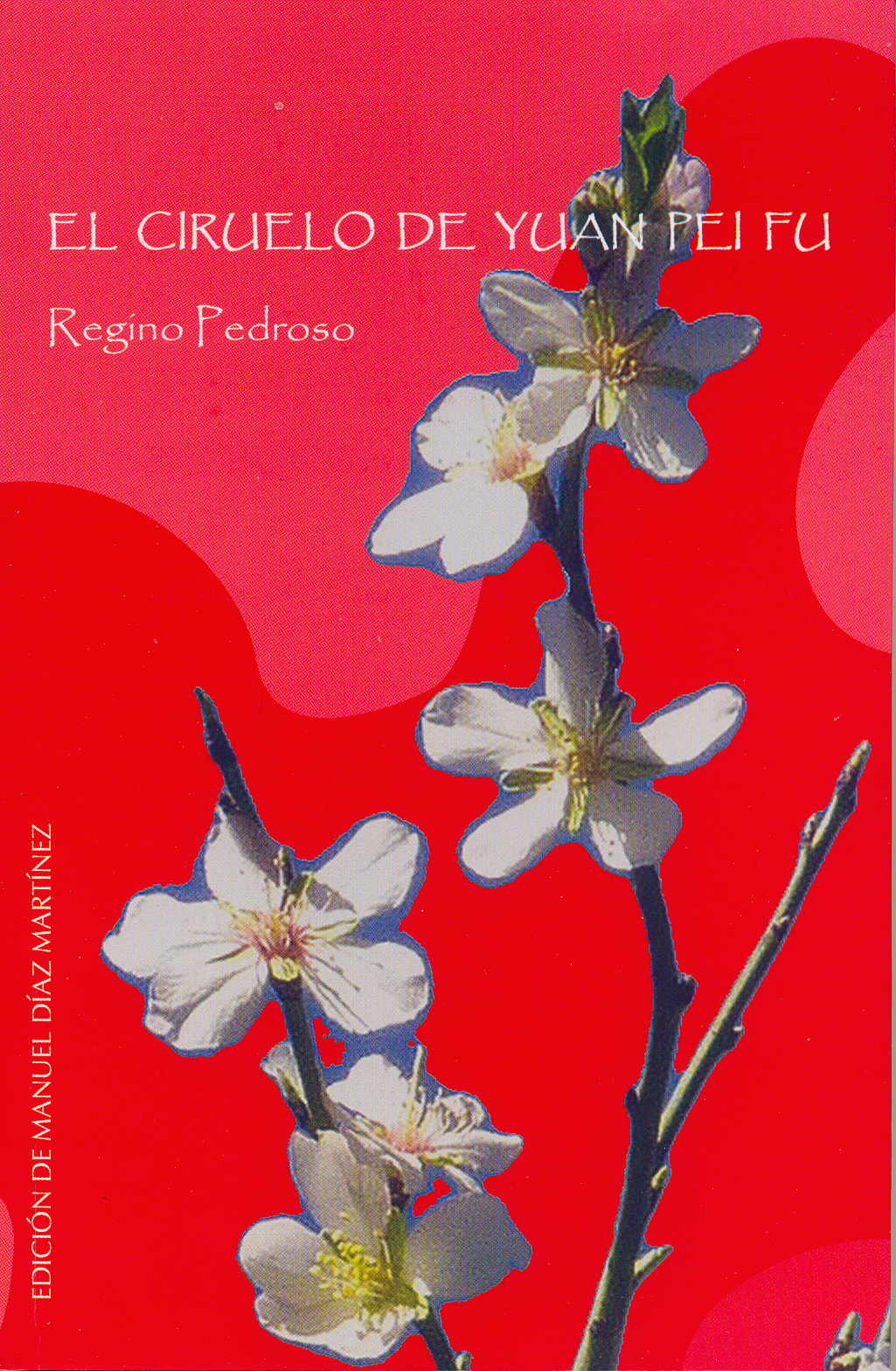

4.1.1.10.7 “Yuan Pei Fu’s Plum Tree”, 1955, by Regino Pedroso

This poetic piece by Regino Pedroso is of more complex exegesis because it seems to distance itself from the national references on which he constructed the social content of his poetry, by proposing as a creative fantasy that these verses constituted the supposed translation of some Chinese manuscripts that he inherited from a remote ancestor.

The book certainly has a colloquial tone, and some topics are approached with a certain irony; however, in them the author captures a tenderness, perhaps without cause or without channel, which transforms his critical stance toward reality—seen through snippets evoked in the dialogue between Master Yuan Pei Fu and his disciple—into a desire for the improvement of humanity, a profound philanthropy, which takes lyrical form in the verse “How I have been afraid that someone would find out that perhaps I am nothing more than a sentimentalist!”

In these verses, the author demonstrates not so much erudition as an assimilation of Chinese philosophy, its epistemological and sensitive roots, in its life-affirming, rather than its abstract, reflective, aspect. Taoism, the doctrine of Confucius, and other philosophical and moral discoveries of this civilization contribute to the creation of a poetic panorama where the semantic and the lyrical merge to a high degree.

Regino Pedroso has attempted to bring part of that ancient culture into the national spirit, but where the aforementioned semantic field goes beyond the Asian and the assembled Cuban identity, to incorporate itself into the flow of universal themes.

In this text, social emergencies are less present, in the sense of the immediate impact of national contingencies on the author; however, the social aspect becomes intelligible from a deeper concern for the human and for conflicts that cannot be reduced to the concept of class struggle, with a treatment of poverty and wealth that refers to the biblical context, broader in that sense, although perhaps less precise.

Although Regino Pedroso published other texts after the Triumph of the Revolution, the essence of his poetic expression had already been captured with great skill in the Republican era and within it “El ciruelo de Yuan Pei Fu” constitutes an unavoidable piece, from which some verses from the emotional poem “Yuan Pei Fu says goodbye to his disciple” are reproduced as a colophon:

“And let your hand never cast anything against heaven.

Nothing should trouble you so much that your sweet peace should become bitter:

I ran, I called, I searched, I forged dreams, greatness…

But naked as I came, the great shadow awaits me.

The more a man achieves, the more sparing he becomes in gifts:

One is never richer than poor in riches…

And be humble, my son, without useless pride;

humility brings happiness.

Be like those river stones

who sing as they jump into the stream,

polished, smooth, flat

from so many shipwrecks, always rolling.

And if a high barrier stops your path,

Do not try to force anything, just go around the wall;

Nothing knocks down a man that he does not raise up afterwards.

And do not ask, do not question anything, disciple;

nothing responds to anything.”