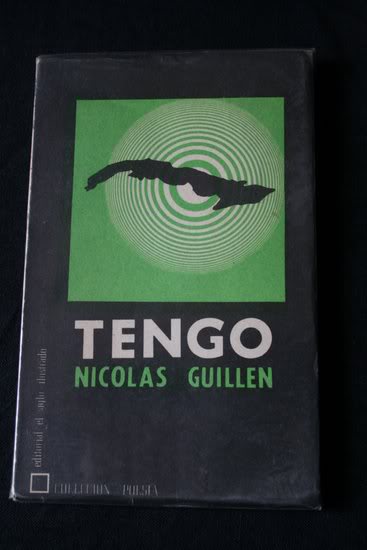

4.1.1.14.9 The poetry collection “Tengo”, by Nicolás Guillén, 1964

After the triumph of the Revolution in 1959, Nicolás Guillén promptly returned to his homeland. Although he was not directly linked to the revolutionary movement, the affinities between it and Guillén’s social aspirations, the utopias somehow captured throughout his lyrical career, took shape in his revolutionary work, of whose most significant actions he was an authentic and fervent singer.

“Tengo” is a testament to the collective emotional state that followed January 1, 1959, and that had been brewing since the period of struggle, amid growing confidence in victory. Racial integration, the vindication of the dispossessed, the break with the previous political system, and the end of North American hegemony, all present in the revolutionary discourse, gradually begin to materialize, anchoring Guillén in his circumstances, in immediate reality, with a hallucinatory poetic woven from the social pulse.

In all this, the only shadow is the danger of sustained imperial pretensions, the aggressions of all kinds carried out or sponsored by the Empire’s henchmen, which sometimes imbue his lyrics with a tremolo trembling but without undermining the foundations of his confidence.

The collection of poems is made up of four sections, titled “Sones, sonetos, baladas y canciones,” “Romancero,” and “Sátira,” plus an inaugural section consisting of 19 poetic pieces. This first section represents the author’s reverence for the arrival of a new era for the nation. In this sense, it establishes an antithesis between the present and the past, the latter with its burden of racism, colonialism, and imperialist domination.

The so-called multiple self that has taken shape in other Guillenian productions, here takes on its true meaning insofar as it is fostered by the established social order, the abolition of prerogatives and castes that truly impeded the flourishing of a common good, of a poetics that could truly represent the feelings of all, previously prohibited by the antagonisms of social classes.

Although there are some texts born in complex circumstances from a historical point of view, such as “Responde tú…” in which he criticizes those who made the decision to emigrate, others present a high aesthetic flight, in this sense the most representative and transcendent poem for the popular sensibility is the one that gives title to the collection of poems, which expresses from the singular poetic self the recovery of one’s own country, secularly dominated by the Spanish metropolis and usurped for more than half a century by foreign interests:

“When I see and touch myself

I, John with Nothing just yesterday,

and today Juan with Everything,

and today with everything,

I turn my eyes, I look,

I see myself and I touch

and I wonder how it could have been.

(…)

I have, let’s see,

that I have already learned to read,

to count,

I have to have already learned to write

already think

laugh now.

I have to already have

where to work

and win

what I have to eat.

I have, let’s see,

I have what I had to have.”