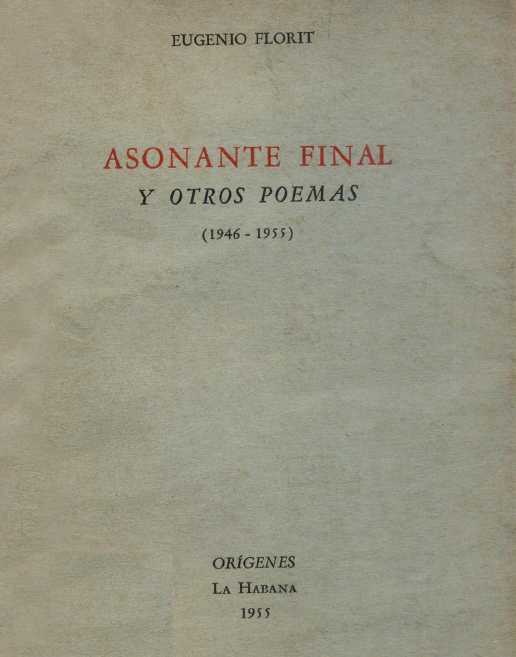

4.1.1.15.4 The poetic text “Asonante final y otros poemas”, 1955, by Eugenio Florit (1903 – 1999)

Some critics consider this to be the most important collection of poems in Eugenio Florit’s lyrical legacy, and not “Doble Acento,” as it was once considered. In this text, Florit somewhat abandons intimacy through a more colloquial tone, in which he expresses from the outset a religiosity evident in his interlocutions with divinity, from “the low” to “the high,” or also from a supposed communion with God, where an inclination for the earth and its people arises: “Forgive me, Lord, this desire to come down from the heights.”

From the time of writing the collection, Roberto Fernández Retamar would express: “Florit’s poetry has completely moved away from that initial yearning for purity. The narrative has reappeared, while formal flourishes have been abandoned, in search of a verse of great simplicity, closer, more to prose than to conversation.”

The conversational nature of the poem brings it closer to the tones and themes of Cuban poetry, a communicative desire that hadn’t been fully expressed in previous collections; however, here, communication isn’t established a priori but is based on a stark lyricism that dispenses with culturedness and even the pretensions of aseptic beauty typical of purism.

One of the poems that in some way inaugurates this trend in Florit’s work is “Conversation with My Father,” where he also abandons the transcendentalist attitude through the evocation of an everyday life partly lost due to the death of his father, where the cult nevertheless constitutes a contained form of nostalgia. The tone of this poem certainly brings it closer to the poetry of José Z. Tallet and others from the Cuban Parnassus, from which some verses are transcribed:

“And we all continue living

and you see, remembering you every day.

and we say: he liked this dessert,

and he walked like that, because he always went quickly,

and once he shaved his mustache

and immediately left it again.

(…)

At my age I prefer

get home and hang up your coat and hat,

and drink a cup of tea with lemon

or chocolate by the window.

Since thank God I’m not cold,

I calmly leave

let the cat do whatever he wants.

And what about the cold and the cat?

has nothing to do with it,

the point is to pass the time

“You and me and whoever wants to read me.”

For Florit, death is associated with the conceptual background of colloquialism, as it makes it everyday, “convivial,” and at the same time it is inserted into her sense of religiosity as the path to God, that is to say, in it the threads of the everyday and the transcendent are united, they are definitively interwoven in her poetics to open a creative space with a broader perspective, where the world now fits and, sideways, human suffering; although Florit has not captured it from its social angle.

It has been said that Florit was a poet of three homelands; and there is no doubt that, despite his thematic and stylistic ties to Cuban poetry, his vocation for universality would go further in his knowledge and poetry. Perhaps his true homeland, evoked from his earliest texts and whose throbbing or reminiscent waves have bathed his poetry, was undoubtedly the sea, a nameless ocean evoked from every shore:

“They broke the sea for me, they took it away from me

to leave me here alone and without air,

without all that was mine:

the foam and the coral and the seagulls.

My sea, where are you? Where do you resonate?

What ship will feel your cold fingers,

your endless word?

You were the sea for me, for my arms

crossed on a wooden chest

that even sank into you, pierced you

and I separated you in moving foams.”