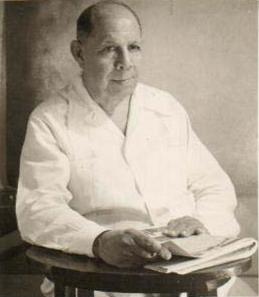

4.1.1.2.1 “Mental Arabesques”, by Regino E. Boti (1878 – 1958)

The title “Mental Arabesques” seems to allude to a mere intellectual exercise or even a rather playful conception of poetic exercise, however nothing could be further from Regino E. Boti’s purpose of shaking the dormant core of our poetry, which was captured more as a light on the path that Cuban lyric poetry had to follow and not as a superior workmanship in the formal aspect.

The text was published in 1913, but its earliest poem dates from 1904, so its unity also expresses a course and a multiplicity given by the sections that comprise it, around dissimilar ideological and thematic lines, with the subtitles: Coats of Arms, Pantheistic Rhythms, Soul and Landscape, Erotic Hymnal, and Autumnal Lyrics. In this sense, pantheism, as the philosophy of a god extending to all created things, is latent in almost all of his poetry.

As a prologue, he expresses in a text that constitutes a programmatic announcement of the new poiesis that was emerging in the tellurism of the nation, entitled “Yoism. Aesthetics and self-criticism of mental Arabesques” the aesthetic and philosophical foundations of his art, the way in which he resolves the contradictions between poetic impulse – he goes so far as to describe himself as impulsionist – and formal chiseling and among others of what can be called antithetical pairs.

This is considered by Cuban literary critics to be the most important collection of poems published in Cuba after Casal’s poetry. Although it is not experimental in the sense that is attributed to the term today, it does possess a desire for renewal in terms of the attempt at new channels of expression, through the internalization of the individual self, the search for conciliation between tradition and originality.

José Lezama Lima, in a selection he made of what he considered the 100 best Cuban poems, included a poem from this work, entitled “Funerales de Hernando de Soto” (Funerals of Hernando de Soto), which has been approved by other anthologists:

“Under the shadowy banner of a silent night

that the bright stars adorn with lights,

The Mississippi mimics a great, merciless duel

dragging its silent and dying waters.

From the wide boats a sail is felt;

an indecisive row of smoking torches springs up,

and advances through the lymph like a living heap

that strange burial without crosses or singers.

The cortege stops. The barges charge at each other;

when the torches are lit, the faces light up

and the breastplates that the high retinue wears shine.

A hundred spears nod. The cochlea throws its claws.

and between the turbid waves that sometimes crash

the coffin sinks and the prayer rises.”

Emotional distancing prevails in the lyrical subject of this text, as a way of objectifying his visions. The vocabulary is presented rather obscure, although it does not hinder the reader’s understanding. This deliberate obscurity, although not of meaning, is also due to the intellectual charge that it gives to the poem above any emotional depth.

Mental Arabesques is an uneven text not only in terms of its poetic postulates but also for its conjunction of the transcendent and the dispensable in art. José Manuel Poveda includes it among the three most important books of this period, stating that in it “there are the beginnings of a new verse that ignores its secrets and that proceeds somewhat gropingly, but that undoubtedly ascends toward heights not yet reached.”