4.1.1.27 The so-called “pure poetry” and its practitioners in Cuba, from 1927 onwards

The definition of what constitutes “pure poetry” and the aesthetic canons of the movement were not exactly defined even in its generative centers in Europe. The same is true in Cuba, especially considering that it would arrive somewhat late to our shores, driven in part by the cultural work of the “Revista de Avance,” always ready to capture the revitalizing artistic winds.

The movement implies a purification of both form and substance, with the elimination of everything that can be expressed through prose. In a general sense, it entails the poet’s rupture with his circumstances, the concrete, the immediacy, to enter the universe of words; with all the contradictions that these uncompromising principles would imply, ultimately with the germ of self-destruction, where silence would be the perfect poetic ideal, the uncontaminated par excellence.

The line of pure poetry constituted an expressive channel opened in Cuba by the upheavals of the avant-garde, toward which many of the poets who once communed with the movement would drift. The very question of poetry per se was already implicit in the avant-garde’s lexical interplay, which would lead to a poetic zone composed solely of words, of an impossible immanence, but which, despite its philosophical impossibility, entailed important discoveries and works for universal lyricism and specifically for the island.

In addition to the aesthetic roots of the movement, in Cuba it was also linked to oppressive political circumstances, from whose influence the poet could not escape either, and in this sense purism is largely the sustained attempt to evade circumstances, to deny the surrounding reality through immersion in the poetic oasis, but the poet has to breathe and what he breathes is precisely his circumstance, transmuted but latent in the poem.

The very coexistence of the avant-garde and the dawn of pure poetry in the Cuban context makes it difficult to define aesthetic precisions regarding the evolution and succession of poetic panoramas and the classification of authors into one movement or another, which is by no means exclusive.

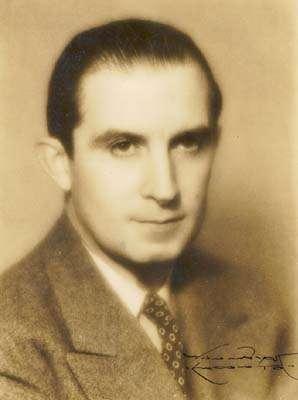

Mariano Brull is considered to have been the most assiduous cultivator of this trend, beginning with the publication of his poetry collection “Poemas en menguante” (Menguante Poems) in 1928. However, these poetic seeds were already present in the works of José Manuel Poveda and Regino Eladio Boti and have been replanted by others throughout the history of our lyrical poetry.