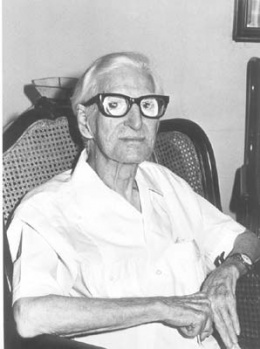

4.1.1.8 The poetic work of José Zacarías Tallet (1893 – 1989)

José Zacarías Tallet did not assiduously cultivate lyric poetry; in fact, he completely ceased this work in the last years of the Republic, although he would return to it after the Triumph of the Revolution, when what had been a “sterile seed” seemed to have the possibility of germinating under new historical and social circumstances.

His only book during the Republican period is entitled “The Sterile Seed”, published in 1951, when in terms of aesthetic and political criteria he really responded to an earlier period, to the generation of the 1920s, associated with the Minorista Group and the aesthetic renewal around the transition between modernism, the so-called “pre-avant-garde” and the avant-garde itself.

José Z. Tallet’s poetics breaks with modernism in that he takes the everyday and immediacy as his poetic object, with an ironic perspective that shares philosophical affinities with that of his friend and brother-in-law Rubén Martínez Villena. However, what stands out in Tallet is his authenticity, the poet’s pouring out of his contradictions, a certain fragmented self that does not aspire to recompose itself for the reader but rather to present itself as it is.

The poems that comprise “The Sterile Seed” had, for the most part, appeared in publications from the first half of the 20th century, such as Grafos, Atuei, Revista de la Habana, Alma Máter, Social, Carteles, and Revista de Avance; however, not with the organic structure that a collection of poems implies. Therefore, while the so-called “critical decade” influenced Tallet, he did not influence the intellectual and literary world with the same force as if he had planted the seed in time.

The book begins with a kind of parable, with a homologous title, in which the lyrical subject perhaps coincides with the author himself, as can be seen in some stanzas:

“The sower, a lad brimming with happiness,

in the ineffable dawn, to the garden of life

He went out to sow. He walked hurriedly.

and a strange smile lit up his face.

He carried his golden seed in a golden basket

which he held firmly against his left side;

and so, when he threw a pile of seeds,

to take them from the heart seemed so.

(…)

Once again the deluded sower lay down

to wait for the moment to reap its fruit.

He saw the longed-for spring pass seven times,

and in vain seven times he waited for his harvest…

…and only a wasteland was his vast field,

interrupted at times by the occasional thistle…

The sower got up and went away, little by little,

and a strange smile darkened his face.”

Almost all of Tallet’s poetic work was marked by a certain pessimism, which increased over the years due to the lack of prospects for a renewing social movement. By 1951, this attitude seemed irremediable, and yet there always remained a tiny glimmer of hope, a “return to the garden” in case a different alternative might one day sprout.

Regarding the poet, Guillermo Rodríguez Rivera said: “I believe there are ample reasons to consider him today as one of the transcendental figures of our contemporary poetry. It is no coincidence that interest in Tallet’s work is growing rather than waning, nor is it a coincidence that the last two generations of Cuban poets have approached his work with interest and admiration.”