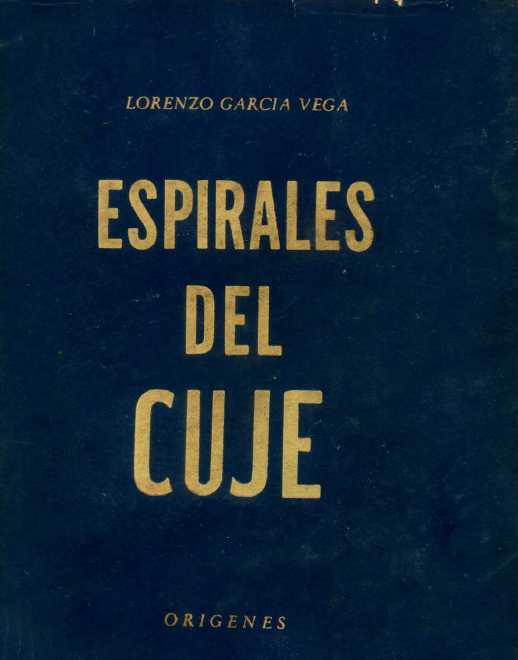

4.1.2.11.3 The work “Espirales del Cuje”, 1951, by Lorenzo García Vega

Lorenzo García Vega dedicated this work to José Lezama Lima—as a testament to a friendship forged in the heat of Orígenes—which he associated with the classification of “stories,” even though they are interconnected in a single narrative sequence. The everyday life of Cuban life erupts in these pages, in which the prose has not entirely shed its lyrical quality.

From the prologue, this purpose of searching for the roots, from the hallucinated memory, for the seed of the author’s identity, is anticipated, in “El Cuje” and other interconnected areas, but whose social and natural essence can be extrapolated to the entire country and from it establish the features of national identity.

The text elevates the entire literary heritage accumulated in the 19th century, surrounding the criollismo movement, to a higher aesthetic summit. However, in this piece, the apprehension is not externalist but participatory with the essence of the criollo, from an affectivity that emerges authentically from memory. Already in the prologue, the author reveals his psychic and aesthetic motives:

“Yes, it was knowing through the images of my childhood the joyful madness of words; and it was the same word “Cuban” that came to me to fill the images of my memory with breath; the word “Cuban” that emerged from my memory to bring me the old danzones that were danced at the Liceo. Yes, in the word “Cuban” came the festival of those dances, with their danzones, so stiff, as if they could be danced by distant Creoles of legend. (…)

And so it is to know through my memories the nostalgia for places, for the land, and it is the coming of questions to scratch at us the anguish of being in all that proliferation of memories; it is the need to know ourselves through the nostalgia of our stories, our anecdotes.”

The anamnesis begins with the adjective brushstrokes with which Lorenzo García draws the town of Jagüey; the insistence on childhood alludes perhaps not only to the plane of reality of bustle and games but also to the stage of the poet and the text itself, of a simplicity, however, that does not fit with his searches in the strictly poetic sphere.

In addition to the lost landscape – a kind of lost paradise – the poet saves from obliteration the houses, the names, the mixture of presences and absences, the evocation from the plane of reality of the people of his memory, also of purely imagined glimpses, all of which enriches his discourse from the point of view of content, without incurring in aesthetic desires per se but simply bearing witness to his emotion.

The poet’s nostalgic inquiry into the past, the slumber of the playful childhood illnesses he suffered, and the mothers and grandmothers, lost guardian ghosts, all converge in these verses, which simultaneously serve as bridges to the dawn of his island, the inextricable interweaving of his identity with the national being that transpires in each of the landscapes and its people.