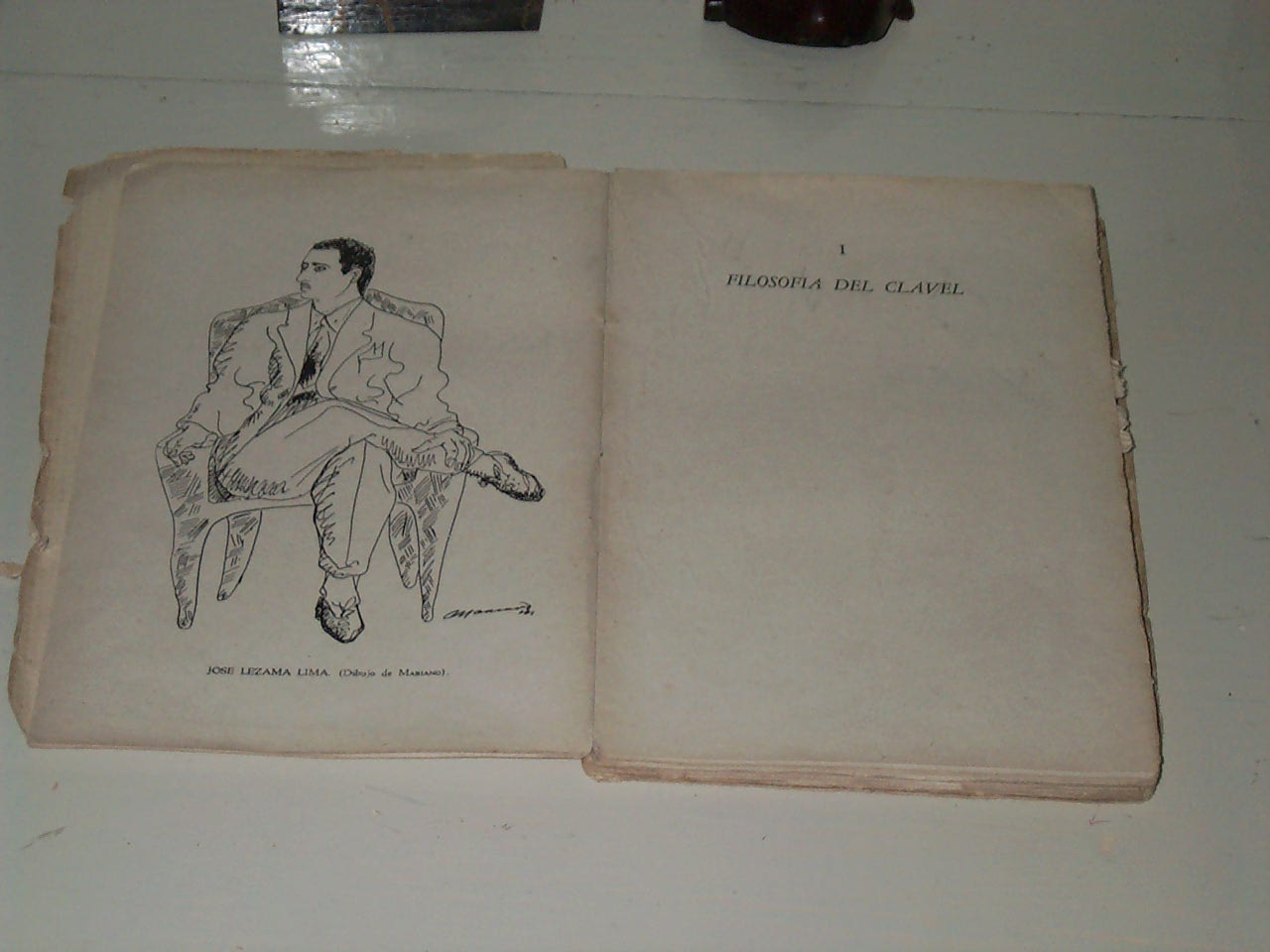

4.1.2.2.2 “Enemy rumor”, text published in 1941 by José Lezama Lima (1910 – 1976)

Regarding “Enemigo rumor,” Lezama Lima says in an interview, “The book was received with relative indifference, which is almost the only critical sense we have and show, but, nevertheless, in what was the nascent state of sensitivity at that time, the book had a pleasant resonance. The younger ones—even at that time I was amazed that there could be someone younger than me—revealed a great, sympathetic curiosity about the things I did.”

This relative resonance that the book had in the Origenist Parnassus and in broader circles of Cuban literature and culture was due in part to the consolidation of a way of speaking that broke with the usual canons, but not only in a purely aesthetic sense, but also due to a background of ideas in which poetry itself became the object of metaphysical inquiries, which was also accompanied by an unprecedented verbal arborescence.

The metapoetic then begins to accompany his lyrical signs, thus revealing a somewhat more vigilant approach to free poetic discourse, in the sense of a cognitive apprehension of reality—poetry implicit in it—which takes precedence over the affective, generally little evident in Lezam’s work. Sensory enjoyment extends even to the realm of language, in the quasi-palatal nature of the words, despite a certain harshness.

A poem that, in addition to other multiple meanings interwoven in the verses of a work of infinite polysemy, shows the poet’s attempt to reach the ultimate substance of poetry, its definition in the intellectual aspect but one could also say its flavor, in short, the most intimate chord that its cultivators of all ages have wanted to touch, is precisely “Ah, que tu escapes”, from “Philosophy of the Carnation”, mourning and at the same time the poet’s compulsion to write:

“Ah, that you escape in the instant

in which you had already reached your best definition.

Ah, my friend, that you do not want to believe

the questions of that newly cut star,

that is dipping its tips into another enemy star.

Ah, if only it could be true that at bath time,

when in the same discursive water

the motionless landscape and the finest animals bathe:

antelopes, snakes with short steps, with evaporated steps,

They seem to be in a dream, without any desire to get up

the longest hair and the most memorable water.

Ah, my friend, if in the pure marble of goodbyes

you would have left the statue that could not accompany,

Well, the wind, the graceful wind,

“It stretches out like a cat to let itself be defined.”

The elusive essence of poetry then unleashes the eternal siege that is also the desire to penetrate the unknown, to extend the limits of what is possible in terms of poetic knowledge of the world, which is expressed in other texts that make up the poetic collection, among which we can mention “A dark meadow invites me”, “Nocturnal fish” and “Ashes remain”, the latter permeated by the imaginary that has replaced reality.

In a general sense, the collection of poems represented the poetic establishment of a form of expression unprecedented in its plurality and dissonance, which would find numerous epigones over the years and even poets of his generation who shared his aesthetic creed without mimesis but as a compass for authentic and personal inquiries, such as Eliseo Diego, Cintio Vitier and Gastón Baquero.