4.1.2.3 Life and literary work of Virgilio Piñera (1912 – 1979)

Virgilio Piñera was always, unfortunately, a marginalized or self-marginalized man, both during the Republic and after the Triumph of the Revolution, although in different ways, both economically and socially. He cultivated his talent in the midst of poverty and poor public education, the only one he had access to given his social status, and gradually gained a reputation associated with the quality of his work but also with the strangeness of his personality, a certain solitary eccentricity.

As is well known, he briefly associated himself with the Origenists—considered by some to be the dissident of Origen—which did not imply that he shared the group’s underlying ideas, but rather was situated at the other end of the group’s common, but not monolithic, aesthetic proposal. The fundamental differences were the poetics of the inconsequential cultivated by Virgil and also his lack of religious affiliation. In the case of the other members, religiosity appeared interwoven with the poetic representation of inner and outer worlds.

After leaving Orígenes, he traveled to Argentina in 1946, dedicating himself to small, poorly paid consular jobs for the Cuban office in Buenos Aires. He moved closer to and further away from literary groups, opposing the official cultural sector, which he did through the modest magazine he founded, “Vic-trola,” a parody of Victoria O Campo.

Providential for the writer was the patronage of José Rodríguez Feo, co-founder of Orígenes with Lezama Lima, who had separated in 1954, which also put an end to the publication. Rodríguez Feo, a millionaire and dilettante, then founded the magazine Ciclón and appointed Piñera as its correspondent in Argentina, who collaborated tenaciously and successfully. This meant an opportunity for Piñera to improve his economic status and at the same time his rise in the cultural and literary world, but with authentic merit.

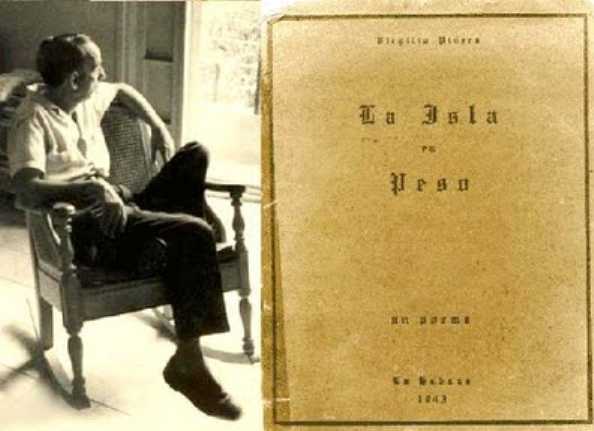

Rodríguez Feo described his first encounter with Piñera thus: “When I was introduced to him, I was deeply impressed by his appearance, so similar to those somewhat ghostly beings that permeate his fictions and leave us wondering whether they might not also be representations of their author: of medium height, gaunt, with a pale and sickly face, and eyes with a restless gaze that reflected that docility we usually associate with perpetually fearful individuals. I was struck by the impression that he was always on the lookout for the unknown or the unexpected accident that might arise as a threat along the path of such a precarious existence…”

Piñera had already returned to Cuba and continued to receive support from José Rodríguez Feo. With the triumph of the Revolution, he began collaborating on “Lunes de Revolución” (Lunes of Revolution), at the request of Guillermo Cabrera Infante, then a newly minted director. Already a recognized public figure, he nevertheless suffered the psychological consequences of the homosexual crackdown that took hold in the 1970s. However, he remained in his country and worked to rectify the errors of that era.

His writing reflects a sense of marginalization, based on his acceptance of his differences with the world in which he lived, which would also materialize into a notable aesthetic divergence. During the revolutionary period, he suffered a certain rise as a public figure, as well as a strange silence regarding his literary output—though recognized by the people—which was somewhat remedied by the countless posthumous recognitions he received starting in 1984.