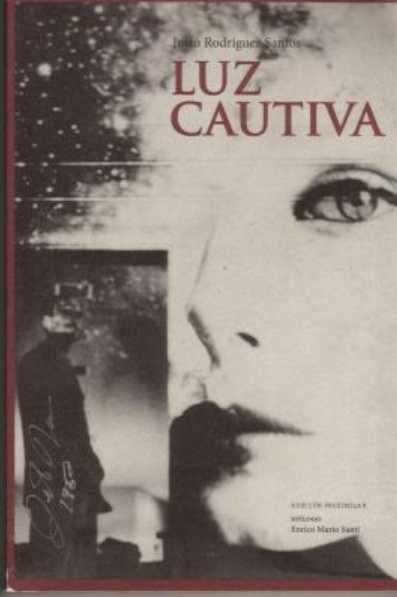

4.1.2.5.1 The poetry collection “Captive Light”, 1937, by Justo Rodríguez Santos

In the collection of poems “Luz cautiva,” published by Justo Rodríguez Santos in 1937, we can already see the characteristics that would permeate his poetics throughout his subsequent creative work, given by classical harmony as an aesthetic container for an immovable serenity of spirit, of liquid resonances. However, the verses move in a monotonous tone, and the symbols display repetitive treatments, hackneyed, for example, in the case of the sea and the rose.

The excessive aestheticism implies a lack of intellectual drive and a depletion of genuine affectivity in the verses. A mastery of the poetic forms of the Hispanic tradition is evident, with a preference for the sonnet and the ballad, but these lack authentic heartbeat, revealing a somewhat impersonal and musically effective writing style.

Many of the verses show a purist affiliation with regard to the cultivation of the lyrical language per se. In the case of the sonnet “The Word”, which largely expresses the author’s own poetics, we can see the cyclical path that led many of the poets of this movement towards the margins of silence, as the pure par excellence:

“Word already forever flourishing

your own life, alien to mine;

butterfly without afternoon or twilight

diluting its invisible diaphanous.

Living plant that rises slender in the wind

lit and confused by the eternal.

Prodigy of a word that opens

ignoring me, sunflowering.

Your luminous color, without color,

from one side to the other contemplating

offers its pure delight at dawn.

Word now poem without words,

Narcissus that is heard

his music is now eternal without sound.”

The formal delight that is appreciated in his verses sometimes takes on a truly narcissistic tone, a self-contemplative beauty that is anchored preferably in the symbol of the rose, which has been stripped by the poet of all earthly roots, to focus only perhaps on the ideal rose.

In his poem entitled precisely “Rosa”, we can appreciate the semantic transfer of elements of his poetic flow and the purist sense of dissolution into nothingness, clearer in one of its stanzas:

“Living silence, always reborn

his crystalline death without waiting.

Pure life, self-possessed,

attentive to the silences of nothingness.”

Even in pieces that seem to refer directly to an emotional plane, such as “Dead in May,” the gloating and reveling in lyrical beauty overrides any sentimental outpouring; the “painful” takes on an impersonal tone, as all other levels of discourse are subordinated to the purpose of producing the immanent beauty of sound.

However, the poem “Elegy” is perhaps one of the finest pieces in the collection and in the entire poetic output of Justo Rodríguez Santos, for it intertwines sentiment with a lofty poetic flight, a deeper emotion that settles but is not annulled in the lyrical flow. This poem is contemporary with the elegies of Emilio Ballagas and has some tonal affinities with them, without the transcendent storm that makes Ballagas’s verses pinnacles of our tradition:

“The rose that dreams of you comes out of the sea

and in memory it floats for a long time.

Air and joy come from the sea,

the breath so pure that it passes through

with a glow of dawn your absence.

(…) In vain the night of death

steal your face from its ancient splendor

to the loving solitude that I live

sobbing your name and the rosebushes.

(…)

Cold silence lies where it rotates

pure star fades from you

and darkness invades the window

where my voice and the wind imagine you.

Living silver from the distant sea sounds

and its corolla language sings

your yesterday as adolescent birches

and the cut flower of your word.

Your profile remains eternal in absence

next to the long minute in which I reside,

already a centaur of light the immense night

over the sleeping valley of your death.

A dull murmur of veins shakes

wet green leaves spread out

and the light and the roots battle

and ash and tears and sleep fall,

while the sob reaches my throat.”