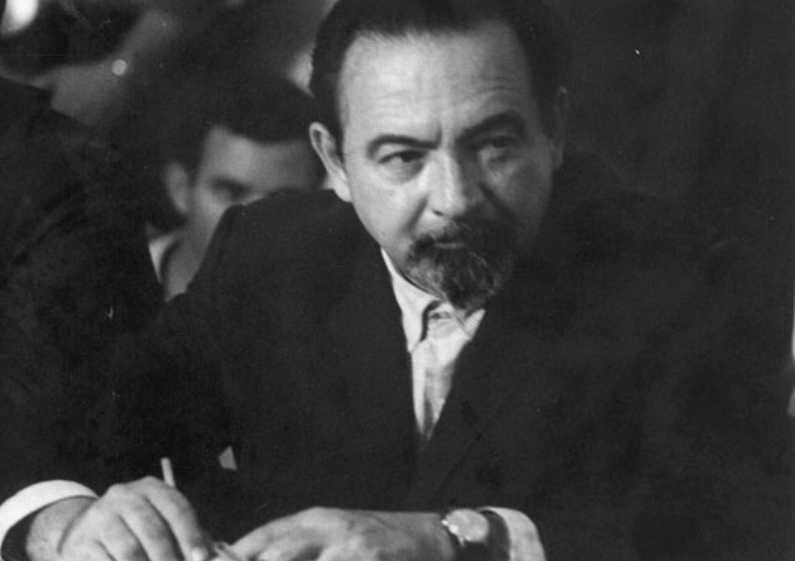

4.1.2.7.9 The prose work displayed by Eliseo Diego (1920 – 1994) before 1959

Eliseo Diego also developed a prose work, primarily narrative, with intrinsic values beyond the lyrical tone that runs through many of his texts of this nature. In 1942, he published “In the Dark Hands of Oblivion,” a collection of pieces that has not been thoroughly addressed by critics but which already contain techniques he would develop more successfully in his next book.

Probably other of his narrative pieces appeared in the magazine “Clavileño”, which had a short life between 1942 and 1943 and published some in Orígenes, under this imprint the text “Divertimentos” saw the light, crucial in terms of the group’s assumptions applied to the field of this genre.

In 1945 he published the story entitled “El desterrado” in Orígenes, in which, around the character named Don Alfonso Muñoz Casas, he describes the last stay of loneliness exacerbated by political exile and lack of communication, in an environment of ancient alienating wealth, of endless corridors that resemble the lost paths of the human mind.

In 1946, he also published “The Day After” in Orígenes, which stems from a certain interplay between dream and reality, similar to the questions in Calderón de la Barca’s “Life is a Dream.” Solitude, in the sense of extreme isolation, and death emerge as central themes here, the latter in a reversal of time from which it can also be interwoven into life, into the intricacies of dreams.

In 1949, Orígenes also featured a number of short works associated with the general title “Friends,” more akin to poetic prose. In lyrical descriptions, he personifies elements of nature, with the titles “The Sea,” “The Fish,” “The Night,” “The Clouds,” “The Wind,” and finally “Horror” and “Friends,” in a succession of images that also capture essential themes from Eliseo Diego’s work, as in “Night,” which he dedicated to José Lezama Lima:

“The night is a poor man’s coat, hanging, torn and thick, in a dark corner.

Through its cracks filters the magnificent glow of the hearth, and it is moved by the gusts of the distant celebration and the deep voice of the servant who fed the poor.

There comes a time when he will slowly pick up his coat, when the light descends, between the leaded glass panes, to the golden dust in the corner.”

In 1955, thus concluding the Origenist period of his narrative and bringing the era to a close, he published “The King,” in which a chess game and its pieces slowly merge with the events of reality. Eliseo Diego’s narrative work here already displays maturity in his handling of plots and their timing, thus complementing his increasingly extensive command of vocabulary and the creation of dreamlike atmospheres that contain nightmares.