4.1.2.9.12 “The date at the bottom”, 1981 and the last verses of Cintio Vitier (1921 – 2009)

“La fecha al pie,” published in 1981 but containing pieces conceived by Cintio Vitier between 1968 and 1973, was dedicated by the bard to the Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal and shows that the Cuban poet has allowed himself to be won over by the latter’s forms of poetic expression, especially in terms of so-called exteriorism; although, as is usual with Cintio, the incorporation is never passive but enriched by its contact with the entire previous poetic cosmos that he had already been taming.

In this collection of poems, Cintio Vitier maintains the conversational tone that he had been developing within his affirmative, revolutionary-inflected poetics. His verses demonstrate the preeminence of impressions over a cold analysis of reality. Life experience becomes a spring that sometimes flows into the confessional, a zone of special vibration within his body of work.

In this collection of poems, the earthly and the religious converge seamlessly, in a worldview that includes justice as a structuring axiological element. The poet then seeks a poetry of reality that is not reducible to the poetic word per se and shows himself participatory and moved by his environment, both natural and social.

The collection also contains some examples of civil poetry, but all of this is incorporated into his personal expressive creed. This is the case in “Lenguaje del Moncada.” As some critics point out, the excess of thought conspires against poetic effectiveness, though not sensationalism; nevertheless, the lyricism translates into a predominant intellectual purpose of poetic apprehension.

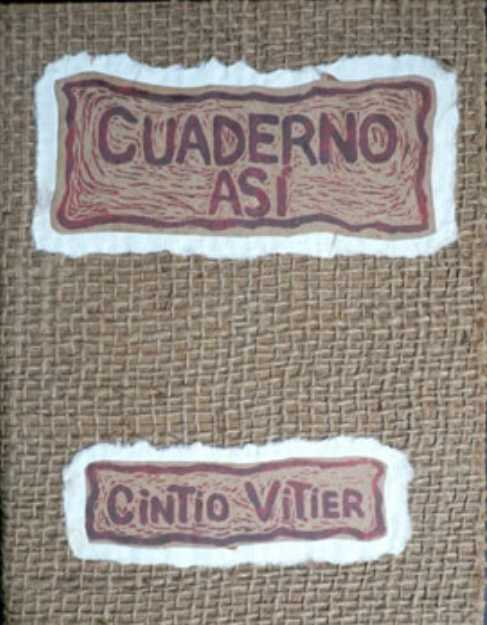

During this period, he also published a long poem in “Journey to Nicaragua,” thus contributing to the collection of poems written mostly by his wife, Fina García Marruz. He also published the notebook “Lost Leaves” in Mexico and published the texts of “Nupcias” and “Un extraño honor,” which maintain a sense of complete integration into the surrounding reality, especially natural reality, as seen in the poem that gives title to the last of the aforementioned collections, which serves as a culmination of his remarkable poetic career:

“The tree knows, with its roots and its branches,

everything that can be a tree:

Or is it also missing?

to its visible half another splendor

What is it that you are suffering and longing for?

We don’t know. But he

It doesn’t need to be known. It’s enough.

May your mystery be without words

that they go and tell him what it is, what it is not.

The tree, majestic as a tree,

full of identity to the tips,

can measure himself face to face with the angel.

And who will we measure ourselves against?

Who will share our sorrow?

Look at that face, examine that look.

where what shines is a void,

review as in dreams

those painful lines around the lips,

that furrow that must deepen on the cheek,

the desolate beach in front,

the nose like a baleful tomb. What a devastated kingdom,

What a fierce and melancholic wreck, still smoking!

Only another face could understand it.

Thus we look at each other face to face, our souls flayed,

with the secret unfathomable joy that founds us,

which is made of shame

and of a strange honor.”