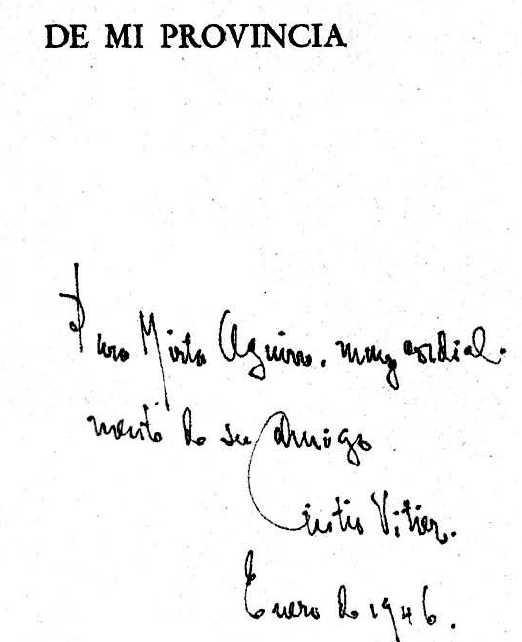

4.1.2.9.3 “From my province”, a collection of poems published by Cintio Vitier (1921 – 2009) in 1945

The short notebook “From My Province” was published in 1945 under the “Orígenes” imprint; it consists of two sections, the first titled “The Successive Sphinx” and containing a poem of the same name and another titled “The Son.” The second section is also titled “From My Province,” with a poem of that name and others titled “The Horse,” “Not as a Temptation,” “Letter,” and “The Waltz.”

In this collection of poems, one can appreciate a dazzling effect, inspired by the very sound and formal structure conferred by the words. In this sense, it produces a feeling of ecstatic beauty, without ceasing to delve into reality. However, the poet’s gaze is captivated by the creatures and he does not seek to unravel them, as life becomes inaccessible to him in some of its phases. The first of the pieces begins with the following verses:

“You are the crystal and the darkness,

but you also have to see

a leaf that no one sees,

a jar that no one loves. Listen!

The mothers and the maidens come to speak to you

as if you were the king, but you tend to him

the beggar’s hand, that tangled and magical hand.”

The poem has several readings but one can appreciate in it an oracular sense, a knowledge that is that of poetry and that must be linked to all things of reality, from the sensorial (the eyes like a king, the hands like a ragged child, the body to the earth, the voice to the mud, buries the ear in the dry and in the wet…) to apprehend the intricate tangle of what surrounds him but always being the beggar who requests something, a hollow that life cannot fill, without worship of its own saying.

In “De mi provincia” (From My Province), one can discern a nostalgia for situations of yesteryear, characters veiled by an evening air—the dusty child, the bony woman—are as if in the recurrence of evoked time, which the poet cannot penetrate, like the silence of the river where the child kicks, immune to reality; but it also reveals a deficit in society that is both economic and spiritual, a void that is not Piñera’s but rather an absence of something he cannot fully glimpse.

Finally, the final stanzas of the poem “Not as a Temptation,” in which nostalgia acts in a way as a poetic quagmire, a hindrance from which the bard must escape, and this is a vision of poetry as a renunciation of other calls of reality. This is, in a way, the evolving meaning of Cintio’s lyrical work, his ability to transpose the pasts of both speech and life to approach that threshold that expands with each step:

“At that moment I no longer continue nor can I give up,

the richest tablecloths folded and the oranges peeled

in a rapture of loving pain that the waves erase.

Only then do the metamorphoses of my frenzy sing

which always ends up untied by the same leaves.

And one begins to destroy something to make The Verse

and it would seem that it is possible to die and be moved,

but wet between the night the wind vibrates and falls

not as a temptation, not as the wind or boredom,

falls with a language that I must not remember, and detaches me.”