4.1.3.3.3 “Memory of Fever”, 1958, Carilda Oliver Labra (1922 – )

“Memory of Fever” brings together some of the author’s previously published pieces and others previously unpublished; yet it still achieves a complete, functional body of poetry. In this volume, the ease and eroticism, with a highly aesthetic craftsmanship, are heightened to a degree that has few precedents in Cuban female poetry. In this sense, it operates as a reaffirmation of feminine spiritual and carnal feeling, in the face of the crippling effect of the prevailing social conventions of the time.

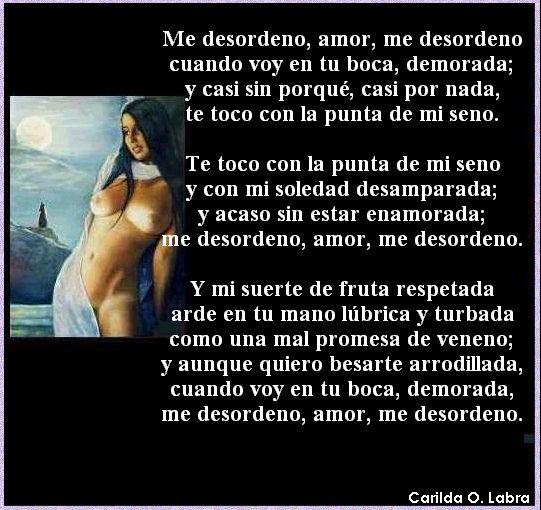

From the title itself, one can intuit a content that is precisely that of the awakening of desire, experienced by a young woman who, at times, assumes the attitude of an “enfant terrible” in terms of her authenticity in capturing the experience of love and romance. This collection includes anthological poems by the Matanzas native, such as the oft-repeated “Me desordeno, amor, me desordeno” and “Muchacho.” The first of these has become worn over time, but that doesn’t diminish its poetic appeal:

“I get messy, love, I get messy,

when I go into your mouth, delayed,

and almost without reason, almost for nothing,

I touch you with the tip of my breast.

I touch you with the tip of my breast

and with my helpless loneliness;

and perhaps without being in love

I get messy, love, I get messy.

And my luck of respected fruit

burns in your lubricious and troubled hand

like a bad promise of poison;

and although I want to kiss you on my knees,

when I go into your mouth, delayed,

I get messy, love, I get messy.”

In “La cita rota” she expresses this poetry of circumstance that rises above itself to offer an unexpected appeal, revealing the old, the everyday that is expressed through hairdressing, lunch, the uses by which she is also defined, for example in the sonnet precisely titled “Carilda,” in which she tries to capture in elusive words her own essence as a girl who dreams.

This notebook was prefaced by another of her aforementioned friends, José Ángel Buesa, who briefly mentions her transcendence as a writer, above the nebulousness of literary accolades. From Buesa’s point of view, this lies in her capacity to be moved by facts and realities that others find indifferent; in short, her capacity to discover, transmit, and vibrate, which distinguish her within the mainstream of feminine poetry. In this sense, she expresses:

“She possesses that singular peculiarity of her own style, which allows us to recognize as her own a poem that has been omitted from its signature. And perhaps for this reason, her work transcends the gallant limits of that special and somewhat subsidiary category known as “feminine poetry.”

In “Llegada de la poesía” we can see the lucid awareness of poetry that, despite not establishing itself as a system, continues to illuminate its lyrical work, which, moreover, was not limited to the realm of amorous delirium but rather alludes veiledly to a kind of social fever, for example when she states that her dress “was beautiful as a revolution,” in “La cita rota,” a poem that appears dated 1946, but this certainly raises doubts as to the political situation and the need for camouflage.

With this work she concludes her poetic work prior to the Triumph of the Revolution, in which we can already appreciate aesthetic successes that make her worthy of appearing in our poetry and the reflection of a feminine, but above all human, sensibility, based on the multiple consideration of beings as equals, before whom she does not use armor of any kind but rather surrenders herself to the experience of life and delivers here a poetic work that reflects the richness of those experiences.