4.1.3.4.3 The poetic and literary work carried out by Heberto Padilla (1932 – 2000) after emigrating from Cuba in 1980

Heberto Padilla continued writing after his arrival in the United States in the early 1980s. The events in Cuba brought him to the attention of intellectuals, who were divided for and against the “Padilla case,” as it was then known. However, his political stance somewhat overshadowed the literary talent he had displayed, regardless of his ideological orientation.

In his early years of exile, he published “El hombre junto al mar” (The Man by the Sea), 1981, and the lesser-known texts “Las catedrales del agua” (The Cathedrals of Water) and “Legacies,” imbued with a deeper colloquial tone than usual, also associated with his experiences within the Revolution and in relation to history, seemingly unintentionally revisiting certain aspects of the Origenist legacy.

The poetic trough of the past and the intended waters of Lethe of that present establish a certain counterpoint, the poet intends to cling to carpe diem and overcome the past but some childhood reminiscence interrupts him, thus reiterating the ancestral dilemma of the emigrant and a relationship with the homeland that becomes ambiguous, but nostalgic in essence:

“I can never avoid that in the least expected hours

a house where I lived as a child reappears.

Some –I remember- were not ugly, but I did not love them.

I wanted to build a wooden shed,

a busy corridor

with enormous mezzanines

where to bury my arrows, my stones

my treasures.

Moving houses all the time

(in childhood and later)”

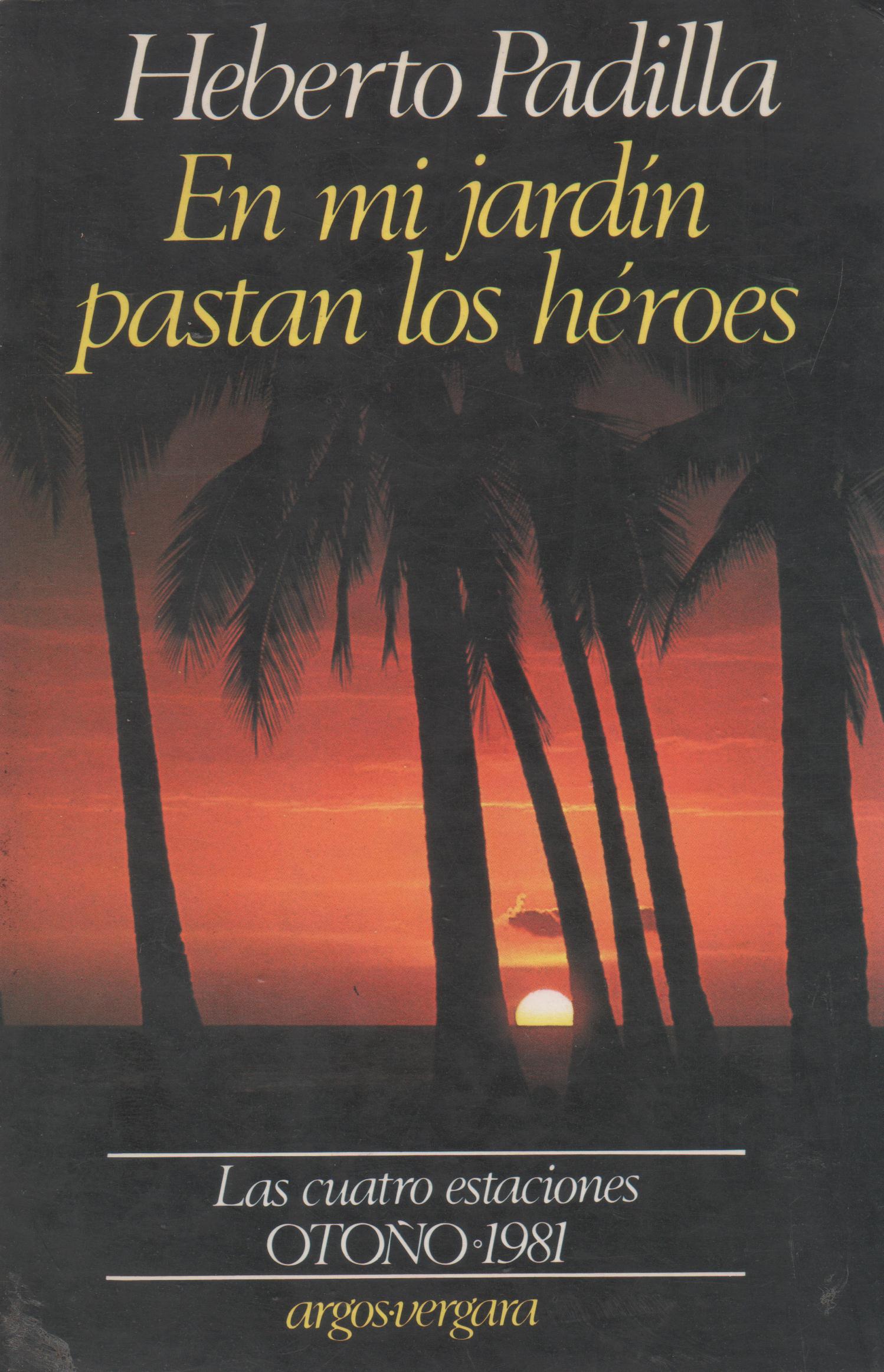

His narrative work is less well-known, beginning even during the period of his revolutionary decline, with “El buscavidas”, a novel published in Cuba in 1963. Already in exile, he would write “En mi jardín pastan los héroes” (Heroes Graze in My Garden), in 1986, and the text “La mala memoria” (Bad Memory), an autobiographical display in which traits of the essay and strictly narrative elements converge, a facet that completes his literary vocation beyond the exclusively lyrical.

His almost final poetic text, “A Bridge, a Stone House,” also contains some clues to his perception of reality and his intimate connection to the island, also recreated in “Dreams Never Come True.” Padilla will always be remembered as one of the most authentic voices of the generation of the 1950s, who emerged from the collective chaos to bear witness to a complex time and his own identity, immersed in the momentum of history.

Guillermo Cabrera Infante would comment: “His death leaves us with sadness because he has died, in addition to a good man, an important poet. And that is the sad thing: there will be no more poems by Heberto Padilla, with his extraordinary way of writing verse.”