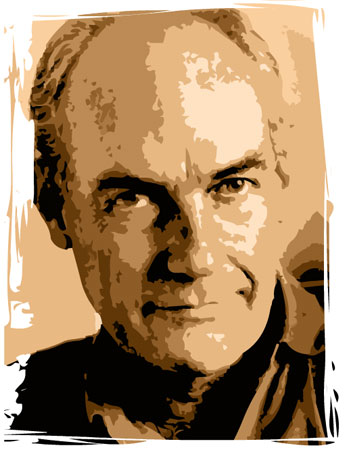

4.1.3.5.1 The literary and audiovisual work of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea (1928 – 1996) after 1959

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s work as a screenwriter and film director focused on critiquing Cuban reality, including its scourges, such as bureaucracy and other ethical implications. Immersed in and fostering the spirit of the new Latin American cinema, he created an audiovisual aesthetic of seemingly chaotic character, contrasting with the formal perfection and value-lacking of Hollywood-inspired cinema and European film tradition, albeit with a latent influence of Italian neorealism.

His film production includes the following feature films: “Stories of the Revolution” (1960); “Twelve Chairs” (1962); “Death of a Bureaucrat” (1966); “Memories of Underdevelopment” (1968); “A Cuban Fight Against the Demons” (1972) (based on the historical work by Fernando Ortiz); “The Last Supper” (1976); “Up to a Certain Point” (1984); “Strawberry and Chocolate” (1993); and “Guantanamera,” in addition to countless short films and documentaries.

However, he also conceived some poetic pieces that, while not collected in a book, are valuable as an aspect of Gutierrez Alea’s cultural work and also express the aesthetic of reflecting real events and characters over a refined formal approach. The Cuban magazine “La Jiribilla” includes some of these pieces by Titón, as the distinguished screenwriter and film director was also known, including “10 Abril 69”:

“The wave is this:

I’m bored by poets who

they are running out of arms

toothless

skinless

without sex

who lose a leg in every fight of love

and in the end only remains

they their crying

inconsolable.

I am disgusted by selfish people who

They suffer from what is called

the passion of love

Love is not suffered,

one lives.

Passion “is not sad because it is true”

It is a disease of the body

that one day she will be cured

with little pills.

And love, on the other hand, is life

same – that which allows us

to be alone – to be alone – to be

ourselves – because it

we will have everything.”

This selection also includes “Time to Pass,” “Meaning of Distance,” and “May 11, 1972,” perhaps due to the custom of titling some poems based on their date of conception. In these, we can see the poet’s immersion in reality, a certain fear that sacrifice might erase his enjoyment of the present (“We continue to rise / and little by little / we pass to a better life”). The erotic also has a weight in this brief selection, which constitutes one of the few examples of Gutiérrez Alea’s occasional lyrical work after 1959.

Tomás extended his cinephiledom, using the term in the sense of a professional love for this art form, to the field of essays, with the work “Dialectics of the Spectator” (1982), which offers a structured view of art and the film industry, from the perspective of public reception, not because of his populist nature but because his films are anchored in the realities of the Cuban people.

Already in the 19th century, more than a decade after the filmmaker’s death, his widow, Mirtha Ibarra, actress and the most important female character in “Fresa y Chocolate”, compiled a series of letters that bear witness to his life as a creator, entitled “Volver sobre mis pasos” (Return on My Steps), also a tribute to the significance of this figure’s career for Cuban and Latin American cinema and, in general, a culture that is captured in an audiovisual poetics of profound social content and high aesthetic purpose.