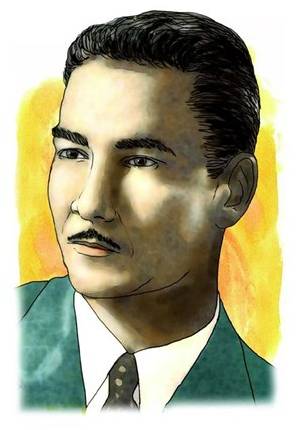

4.1.3.7 The poetic work of José Angel Buesa (1910 – 1982)

José Ángel Buesa was the most populist of the Cuban neo-romantics, admired in his time, even beyond our borders. Critics have almost unanimously accused him of promoting an art form driven by commercialism or perhaps a natural impulse to mass production. However, his works still populate the notebooks and daydreams of Cuban adolescents and young people, an indelible mark of Buesa’s passage through our culture and our sometimes stagnant and narrow-minded approach to poetry.

Some have even described the bard as a phenomenon of mass communication, in his ability to capture in prefabricated moulds that are easily anchored in popular taste, feelings of shared roots, especially with regard to the ups and downs of love, which, like a good neo-romantic, he captures in its diversity of areas and nuances, with a strong dramatic component that perfectly matches the sensitivity of use.

Buesa was born in the province of Villa Clara and from a young age became interested in poetry, theater, and radio, for which he wrote novel scripts based on similar premises to his lyrical works. He was one of the representatives of Neo-Romanticism who exerted the greatest influence on his contemporaries, especially among the urban petite bourgeoisie, who identified with his aesthetic and greatly revered his works.

Among his early works are “The Fugue of the Hours,” 1932; “Babel,” 1936; and “Canto Final,” 1938, in which his neo-Romantic leanings are already evident, but in poems shaped with a certain desire for effect, which incur in the reiteration of words and motifs to please a specific audience; nevertheless, some successes can be seen in his ability to forge poetic images and glimpses of a lyrical gift that did not aspire to higher endeavors.

In the following decade he would publish, in 1943, “Muerte diaria” and “Oasis” –the latter notebook, according to Virgilio López Lemus, was edited 14 times until 1962, which demonstrates the enthusiastic reception of his work by the general public, not only and even to a lesser extent the habitual consumers of poetry-; also “Odas por la victoria” (Odes for Victory), 1943; “Canciones de Adán” (Songs of Adam), 1947 and “Lamentations of Proteus”, 1947, the latter one of his highest quality pieces and one that deviates somewhat from the tone he had followed until then.

These were followed by another series of notebooks without any truly distinctive elements: “Alegría de Proteo”, 1948; “Nuevo oasis”, 1949; “Poemas en la arena”, 1949; “Poeta enamora” (Poet in Love) (made up of two parts that he would publish in 1955 and 1960) and two anthologies also appeared that compile his journey through poetry: “Doble antología” (Double anthology), 1952 and “Sus mejores poemas” (His best poems), 1954, which also constitutes an indication of the success of his works.

The poet left the island in 1960, but he still published three collections of poetry since the triumph of the Revolution: the aforementioned second part of “Poeta enamora” (Poet in Love) and the titles “Poemas prohibidos” (Forbidden Poems) and “Libro secreto” (Secret Book), from 1959 and 1960, respectively. Beyond the facileness, the commonplaces, the thematic and vocabulary recurrence, the charm of his pieces has transcended a sometimes revived romanticism of youth.