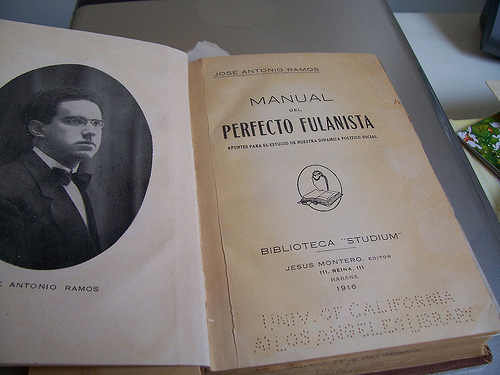

4.4.4.1 Manual of the Perfect Fulanista, by José Antonio Ramos (1885 – 1946)

“Manual del Perfecto Fulanista” (Manual of the Perfect Fulanist) is one of the first works of the 20th century that most deeply explores Cuban reality and national identity within the context of North American economic and cultural penetration and certain disintegrating tendencies of the profound concept of Cubanness, which were evident in the island context. The text was written in 1914 and published in 1916.

According to Marcelo Pogolotti, “José Antonio Ramos demonstrates how electoral politics fosters the selfishness of the masses. The candidate flatters to such an extreme that the voter feels solicited and challenged, forgetting that voting is a duty and that their vote entails a responsibility. They begin to believe that their vote is a negotiable asset that they have the right to sell or exchange for a promise of direct benefit to themselves.”

In the text, Ramos addresses the origins of the political class that quickly formed upon the founding of the Republic, almost all of them associated with veteran independence supporters; but they lacked sufficient talent for governing the Republic and, in fact, did not always possess the same moral stance that the patriotic devotion of yesteryear suggested. Added to this was the fact that staunch supporters of autonomism and notorious fundamentalists had also been called upon to form the government.

In a certain Ramos symbolism, the “so-and-so” is a politician of high demagogic stature, around whom the henchmen, “so-and-so,” gather in search of favors. The political ethos of these figures is depicted with early precision by Ramos, as well as the behavior they would adopt toward the American government and the public treasury.

Ramos points to the existence of a Creole aristocracy that survived the warlike ravages of the previous century as a class, exercising its authority through the flawed political party system. However, it had suffered a certain impact, and in this context, he also criticized the attitude adopted by a significant sector of this aristocracy, who decided to go into exile and safeguard their properties, turning their backs on the fate of the island.

The text constitutes one of the first portraits of the true republican situation and its political background; although the author has not yet abandoned his view of an elite intellectual group that governed society, his first insights into two key points are evident: the attitude of the most erudite scholars and intellectuals did not always aim toward the common good, and these, rather than possessing an infused talent, had far superior educational opportunities, in line with their economic ones.

In the essay “The Perfect Fulanista,” included in the book “The Republic of Cuba Through Its Writers,” Marcelo Pogolotti returns to Ramos’s ideas, somewhat updating them in light of the events that followed the Revolution of 1930. Both are important essay pieces for understanding the neocolonial era and how it was perceived by the intellectuals who participated in it.