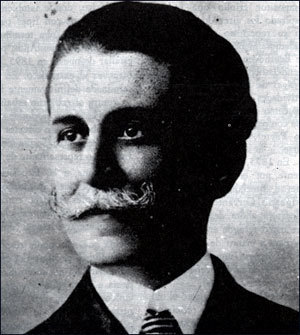

8.4 Leading exponent of 19th-century Cuban music (1868-1900). Ignacio Cervantes.

Ignacio Cervantes.

Ignacio Cervantes is considered the poet par excellence, achieving surprising levels of sensitivity and intimacy. Cervantes is not a classical composer, in the sense of belonging to that musical movement, but his work represents an excellent example of how to transform the traditional into an artistic form. He belongs to that line of Cuban musical composers who made popular elements a component of art and Cuban identity.

He was born in Havana in 1847 and died in the same city in 1905. He began his musical studies with his father, from whom he received his first piano lessons, continuing them with other prestigious teachers such as Juan Miguel Joval and Nicolás Ruiz Espadero. In 1865, he enrolled at the Imperial Conservatory of Paris under the tutelage of Antoine François Marmontel and Charles Alkan. There, a year later, he won First Prize in the Piano Competition, followed by the Harmony Competition, which he won in 1867 and 1868. These achievements confirm his great virtuosity and elevated musical ability.

In 1870, upon returning to Havana, he began a distinguished artistic and social career, joining the independence struggles alongside violinist José White. This led to his expulsion from Cuba and his relocation to the United States, where he continued to fight for his staunch ideals.

In 1879, he returned to his homeland and resumed his previous artistic work as an interpreter of the works of European Romantic composers. During this period, he also conducted the orchestras of the Payret (Prado and San Martín (San José), Old Havana, Cuba) and Tacón theaters in Havana, and distinguished himself as a notable pedagogue, training students such as Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes, who later became a renowned musician.

Cervantes began creating his works at a very young age. His musical output includes chamber music, symphonic music, zarzuelas, and an opera, but he was particularly noted for his dances for piano, in which he captures the essence of Cuban culture. He employs typical Cuban rhythms, including the Cuban cinquillo, and his piano work is more developed, encompassing all its registers. He continues the nationalism initiated by Saumell. It is significant to note the musical counterpoint established between both hands, as the harmonic bass, which frequently appears in the lower register, develops as a melody that occasionally supplants the upper voice.

His works still manage to exude the national element that distinguishes them with relevance. “Adiós a Cuba,” “Los delirios de Rosita,” “Los muñecos,” “Picotazos,” and “No bailes más,” among many others, are representative of the Cuban piano repertoire, and their significance transcends the musical values each contains, as they demonstrate the stylization of characteristic elements of national identity.

Cervantes is studied in the country’s music schools and conservatories; students return to his scores again and again, his books are reissued, while his work Adiós a Cuba endures among all the music in the film Fresa y chocolate (1993), by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, where the theme of the relationship between nationalism and emigration is one of the central themes.

Thus, one hundred years after his death, Cervantes remains, within the broad Cuban cultural spectrum, a symbol of Cuban music.