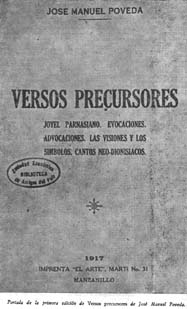

4.1.1.6.1 First lyrical incursions and the poetry collection “Versos Precursores”, by José Manuel Poveda (1888 -1926)

“Precursor Verses” was published by José Manuel Poveda in 1917, but the poems that make up this book date back to 1912. Although the most select of Poveda’s lyrical poetry is concentrated here, he had previously published some excerpts worthy of posterity and where his deathly tendency and a certain vital exhaustion were already outlined, all of which is reflected in his poem “The Twilight of the Condor,” not often anthologized despite its successes, from which the final stanzas are transcribed:

“I couldn’t tell you everything I’ve suffered,

what my effort has been, what my life has been like…

I only know that I am weak and that I am very tired,

and I feel nostalgic for lost happiness.

I only know that even standing on the arid summit,

from the reddish sunset to the flickering glow,

I tremble, groan and sigh under my grief

with a broken claw, with a bleeding wing.”

The collection of poems “Precursor Verses” is composed of four sections: “Parnassian Joyel,” “Evocations,” “Advocations,” “Visions and Symbols,” and “Neo-Dionysian Songs.” Both his innovative concerns and modernist influence are evident in this text; but it goes beyond this and achieves a decidedly unique expression within Cuban poetry of the time, associated with his personal experiences, the filter of his poetic expression.

The influences of Julián del Casal, in an almost inveterate cult maintained by the bards of the time, as well as those of Baudelaire and other European lyricists, are integrated into this work, but achieving a synthesizing style that goes beyond holistic summation. The formal work, the value of poetry per se, does not detract from the sensitivity and intellectual perception of the world that underlie Poveda’s stanza structures.

Poveda didn’t conceive this work as a culmination but rather as an opening toward a new aesthetic; but at the same time, he didn’t believe in absolute originality, but rather in returning to island roots, historical and lyrical, truth and beauty, to rescue and fuse with the present the entire national being, his grand conception of the Homeland, where creative individuality, also made up of the universe of collective symbols, has a place.

The bard could be accused of a certain egotism; but this was only because his poetic awareness and sensitivity allowed him to critically capture the entire panorama around him, preferring the work of Regino E. Boti and his own voice within the long epigonal line marked by the filtration of artistic work by desires for social recognition and other interests alien to the creative essence of poetry.

Nearly three decades after the work was published, in an issue of the magazine “Orígenes,” Rafael Esténger selects some fragments containing Poveda’s criteria on art, beauty, and other topics; and he also notes: “José Manuel Poveda, according to the image conveyed by his Versos Precursores, was not an ivory tower poet: he was more of a man of the agora, and of a noisy agora. He played the role of missionary of literary renewal: he fought for it in the tribune and the newspaper, without forgetting the civil strifes. He used to write the word Patria using a reverent capital letter.”