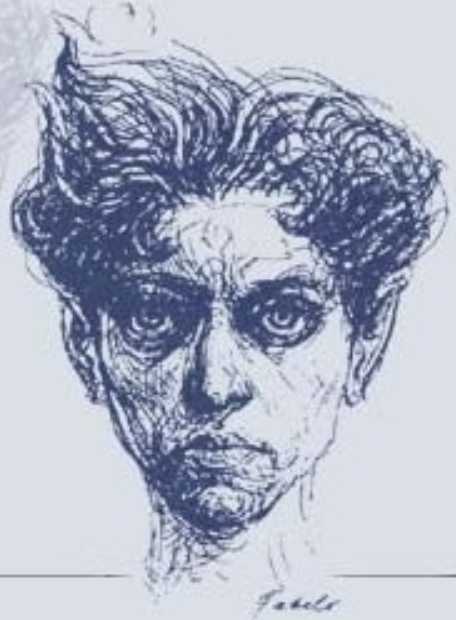

4.1.1.12.1 The poetic work of Rubén Martínez Villena (1899 – 1934), second stage

The period between 1923 and 1928 was the most fruitful from a lyrical point of view, also associated with his political awareness and the adoption of an active and transformative stance in both aspects of his life. During this period, he decisively became a militant poet, but this contributed to the fertilization of his poetics; in this sense, his creative and political work constituted a symbiotic relationship that increased his potential in both spheres.

Written in 1922, but with a breath already corresponding to this period due to the choice of topic and the desacralization of the event of death itself, the “Canción del Sainete Póstumo” (Song of the Posthumous Sainete) is already inscribed at the dawn of the avant-garde due to its substance, although it is not based on the versatility and typographic experimentation typical of this artistic movement.

The poem represents the new vital attitude that Villena would adopt, where sentimentality has given way to a worldview marked by irony, the sublimation through humor of a certain disenchantment with the behavior of the flock:

“I will die prosaically, from anything

(the stomach, the liver, the throat, the lung!?)

and like a good corpse I will descend into the grave

wrapped in a holy shroud of compassion.

Although death is something that happens daily,

a dead person always inspires a certain curiosity;

Thus, full of strangers, the house will be full of bees,

and the whole neighborhood will study my face.

Then there will be the wake; unknown people,

before my relatives, inert from crying,

with the suspicion of someone who knows he is lying

will recite the phrases of common condolences.

(…)

And already at dawn, over the crowd

the solemn concept of “never!” will gravitate,

Then comes the consolation of continuing existence…

And the morning will come… but you… will not come!…”

As revealed in the farce and, more generally, in his entire poetics of this period, there is a need to subvert all surrounding reality. In aesthetic terms, modernist canons were already insufficient for the new sensibility; from a moral point of view, the poet sought to break with empty, inauthentic social conventions; and politically, since the Protest of the Thirteen, in 1923, Villena had embarked on the path of revolutionary struggle on all fronts.

The poet even moves between a certain neglect of form, in favor of the impulse of ideas and the philosophical need to break out of their chrysalis and grow in the spiritual order, as seen in the poem “The Giant”; and a certain formal precision in the sonnet “Insufficiency of the Scale and the Iris,” where the bard achieves a superior quality, which stands in its own right in the history of national lyric poetry:

“Light is music in the lark’s throat;

but your voice must be made of the same darkness;

The wise nightingale breaks down the shadow

and translates it into the sonorous iris of his dirge.

The visible spectrum has seven colors,

the natural scale has seven sounds:

you can braid them all into different songs,

that your greatest pain will remain unspoken.

Dominating the scale, dominating the iris,

you will silence the impossible song in darkness.

It must be black and mute, since your verse lacks it.

to express the key to your secret anguish,

a note, inaudible, of another octave higher,

a color, from the dark ultraviolet region.”

This period of Villena’s life coincided with the emergence of the Minorista Group, of which he was perhaps an essential member, the author of its manifesto, and one of its spiritual guides, if ever there was one. In this regard, Raúl Roa stated: “He lived in verse and for verse (and was), despite his very limited work, the most outstanding poet and the most authentically personal voice of the group.”