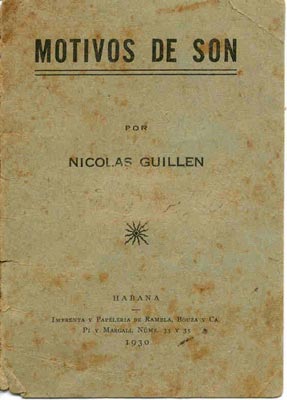

4.1.1.14.1 The poetry collection “Motivos de Son”, published by Nicolás Guillén in 1930

“Motivos de Son” is made up of 8 poetic pieces (this would be the original number, but in successive editions the poet included and eliminated some, finally leaving the same number, but in reality 11 compositions would at some point form part of the collection) full of discoveries that open a new expressive channel to national lyric poetry, according to Angel Augier, “they were more than half a century ago the sensational revelation of genuine Cuban poetry and of a brilliant creator of it”

Nicolás Guillén recounted the mystical genesis of the work, when he mentioned in a lecture given in 1945 at the women’s society “Lyceum”, that the entire collection of poems had been conceived the day after an April night in 1930, when an unknown entity had whispered in his ear the phrase “Negro bembón”, which gives title to the first of the pieces.

Beyond mysticism, emphasis has been placed on an ancestral call of blood and poetry, deeply rooted in Africa, which Guillén was able to perceive in his time. The verses were published in the “Ideals of a Race” section of the Diario de la Marina, in which the poet had regularly published texts that strongly opposed the prevailing racial discrimination, deeply rooted in the consciousness of the upper strata in particular.

There has been an effort to unravel the influences that preceded the conception of the collection, beyond the Guillénian anecdote, old Spanish lyrics, and the work of the Black American poet Langston Hughes; however, Guillén himself points to the influence of the lyrics, spirit, and music—to which these songs are evidently so close—of the Sexteto Habanero and the Matamoros Trio.

Although the collection of poems was restructured several times, the 11 poems that were once included are titled: “Black bembón”, “Mulata”, “If you knew…”, “Keep going…”, “You have to have a lot of balls…”, “Find yourself some money”, “My little one”, “You don’t know English”, “Yes they called me black…”, “Curujey” and “I’m selling myself expensively!”

These poems reveal from various angles the economic situation to which Black people were generally confined, not with tragic overtones, but rather the influence of this background even on romantic relationships. The rhythm, the use of refrains, and the distorted prosody that mimics the speech of the poor—not just Black people—constitute only some of Guillén’s early resources, in one of the key texts in our lyrical history, as it signifies the beginning of cultural decolonization from persistent foreign influences, especially from the United States.