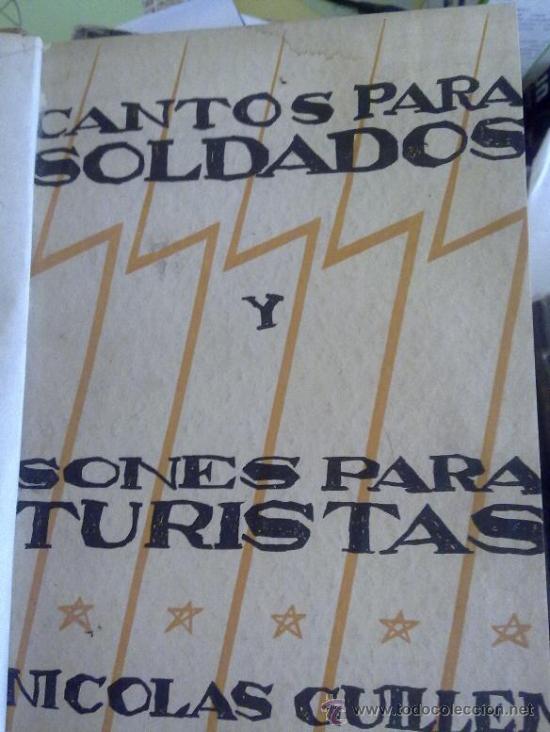

4.1.1.14.5 “Songs for Soldiers and Sounds for Tourists”, by Nicolás Guillén, 1937

“Songs for Soldiers and Songs for Tourists” is a double book in terms of structure and message, although as a poetic text it has many other secondary connotative values that nourish the lyricism of the work.

The section dedicated to soldiers addresses the popular background from which soldiers typically come, forced by petty interests and their own economic status to oppose their own people, sometimes carrying out bloody acts in the name of military dictatorships. Through this, it denounces not only the Cuban political context but also the situation in Latin America, which is often plagued by tyrannical pursuits and enthronements.

“I don’t know why you think, soldier, that I hate you, if we are the same thing, me, you” is a question that was deeply rooted in its time, especially because through the question we can think of a certain primordial hatred of the soldier towards the people in which he had grown up, not because of any kind of malice but because it suited the interests of politics and was therefore encouraged in those spheres, evident for example in the common evictions.

For its part, “Sounds for Tourists” is given by an ironic approach that begins with its very title, alluding to the tourist brochures that sought to promote this economic sector, but for a country development that concerned only the bourgeois sector.

At the time of the work’s publication, the global economic crisis that began in 1929 was having an impact on Cuba, with increased effects due to the systemic deformations of the economy. Tourism had been ironically called “the second harvest,” which was expected to emerge from the critical situation, with the departure of the powerful who, as a rule, “privatized the profits and socialized the losses,” as Mario Benedetti would masterfully state.

In this sense, Guillén’s poetry collection offers a “touristy tour” of Cuba’s marginalized neighborhoods, exposing the sick side of the smiling coin that was supposed to be presented to a foreign audience. Social integration, the emergence of the face of a people above Black culture, is manifest in this collection of poems, both a harsh denunciation and a hopeful expectation; not only from and for Cuba, but also a valid inspiration for all of Latin America.

It’s worth concluding this section with Mirta Aguirre’s opinion, who believes that the text “warned in advance that the book was worth a whole definition of Latin American drama, not just an insular one. It was the uniform of caciquismo, of uprisings, of military coups, of the whip, of the predominance of brute force and contempt for civil power that, like Cuba, all of Spanish-speaking America knew very well. And it was about the pirate who briefly removes the knife from his teeth to bring the neck of a bottle to his lips. Tourism: a seaside, jubilant, vacation-loving face, like an octopus on vacation.”