4.1.1.14.8 “Elegy to Jesús Menéndez”, by Nicolás Guillén

The long poem “Elegy to Jesús Menéndez,” of sustained lyricism that reflects his own dismay and that of an entire people, constitutes, according to many critics, Nicolás Guillén’s masterpiece, due to this very ability to stretch his poetic instrument from the multi-dimensional.

Guillén began writing the text in 1948, the year of the vile assassination of the sugar mill leader Jesús Menéndez, and did not finish it until 1951, so the pain of social loss, the emotion that is poured into the poetry, was settling for almost four years until it congealed into a lyrical piece of profound popular resonance, where the denunciation is wrapped in a lyricism of contained emotion that transcends its own motive to constitute a lament and a war song, against the architects of the neocolonial situation.

The text also intersperses passages of poetic prose and other intervals with some points of contact with avant-garde, in the second section, in which the author refers to the quotations of the New York Stock Exchange, the petty sphere that revolves around profits and brings into it the “Menéndez Blood”, to tacitly illustrate the way in which capitalism is sustained by the strenuous pain of the majority and even by death: “…selling / gushes of anguish, / proclaiming / marketable clots, nerves, bones of that / dismembered rebellion…”

The first section of the poem establishes an identification between nature, from the space of the sugarcane field, and Jesús Menéndez, his work, his struggle, and his life. The personification of the sugarcane, waving their hands to warn him of murderous intentions, also alludes to the people, like sugarcane subdued by a unanimous, voiceless cry, under the spurs of the Yankee in collusion with the politicians, owner of everything, expanding the latifundia.

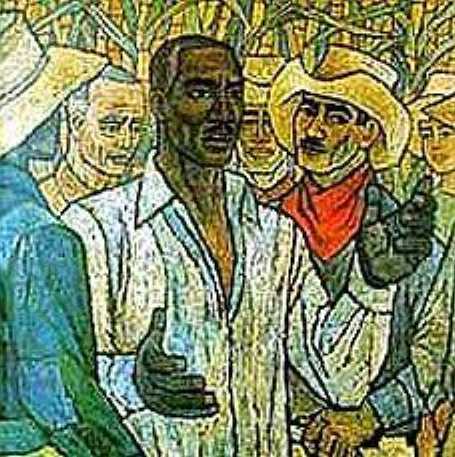

The third section refers to the “Captain of Hate,” before committing the monstrous murder, which it associates with death, to establish an antithesis in the following section through the immaculate, the living that was and will be in Jesús Menéndez. In this sense, it seems to take advantage of the homonymy with the Messiah to give this same sense of savior to Jesús Menéndez, within the context of his Island:

“Jesus is black and fine and mighty, like a cane

of ebony, and has white and courteous teeth,

so his mouth always opens at dawn;

Jesus sometimes shines with sad and sweet eyes;

Sometimes you can hear raging water roaring in his eyes;

(…)

Jesus was born in the center of his island and there

It can be seen from the sea, on clear days,

covered with fixed clouds;

Go up, go up and you will see from its front

with what din it boils at his feet and is renewed

in endless waves of life!”

In the following two sections, passages of poetic prose and highly crafted verse are skillfully interwoven. Here, the analogy between the Jesus of the reeds and the one in heaven is complemented, granting the former divine status, the ability to bless from his death, which is life, and his resurrection in the people’s imagination. In this sense, the last section heralds his metaphorical return, when his ideas have grown like reeds and germinated without return.