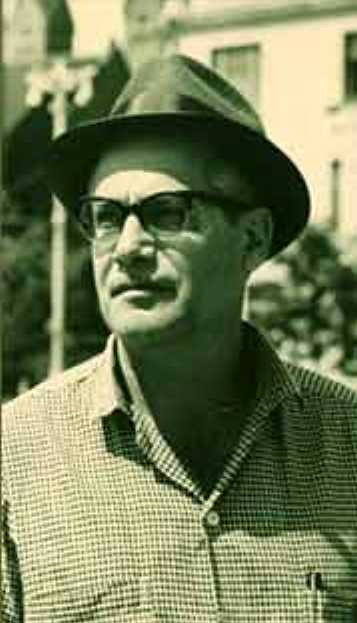

4.1.1.22.4 The poem, “Faz”, by Samuel Feijóo

This poem is another of Samuel Feijóo’s notable poetic achievements, similar in formal design and extensive lyricism to “Beth-El” and his “Hymn to the Allusion of Time.” The poem in question was published in 1956 and is a more peaceful song, the fruit of the author’s mature ideas regarding the exuberance of nature alongside its dark side, all of which serve as a backdrop for human poverty.

The text is divided into three sections. From the outset, topics associated with the decline of nature abound, such as autumn, the barren, and the old. At the same time, humanity, from the perspective of the material works owed to man, also appears demolished by the passage of time, all of which, in some sense, indicates a final season:

“…The trail

The rain has turned the marbles gray; the suns

have gnawed at the joints of the stone, where art

will be bound to the spell. Time

from desolation settles

serene over the dead stones

and the wind that crosses brings

the smell of bitter herbs…”

The second section of the poem depicts a landscape that combines the natural and the urban, as a realm where men parade with their misery. The women of Ciego de Avila—the little black boy, the prostitute, the Chinese shoeshine boy, the black ox driver, the black girls who sell themselves for a handful of candy—constitute brushstrokes that convey a panorama of the economic desolation of the Republic, without any deeper investigative pretensions but rather to record a lacerating reality:

“The corpse of Catalino, a black ox driver,

He gave his suffering face in the poor pine box to the peasants

who were commenting in groups on their disfigurement;

Poor Catalino the ox farmer, without his medicine bottle;

Like his brothers, he was also picked up by tuberculosis on a train

sweats.”

In this section, a colloquial tone prevails, supported by the use of very Creole phrases (throw a little jaloncito at him, the black ajiguagua bounced like a danger, etc.), which denote the author’s intention to reproduce the language of the people and to somewhat concretize his poetry, which is sometimes diffuse in the enjoyment of the landscape.

Black people who are unable to enter the dance also leave a wound in the collective social being, pierced by segregationism that even affects social strata already submerged in poverty, such as the peasants themselves, all of which gives an idea of the position occupied by poor Black people under the weight of such practices.

In the final section, the sea floods the verses, perhaps in a sense like water washing the islands, suggesting their ultimate meaning. Love is a breath that runs through the entire poem, not as a presence but as an evoked subject. The poem also constitutes a lament for disconnection, something that has damaged the relational core of everything on earth, intelligible in these verses:

“How can I return to dialogue?

cut off? How can he get through?

the spaces of ice, heartbreak,

the ancient fall of rain,

to the isolated vision, erect and pale,

whose memory cannot be a gem?”