4.2.9 The narrative work of Miguel de Marcos (1894 – 1954)

Miguel de Marcos’s narrative approach begins with “Palpitations of the City,” published in 1912. In this work, he addresses the city environment from a descriptive yet investigative perspective, understanding the interaction between the social and the individual as a determinant of personality. The city’s contrasts are captured with a certain impressionism and a vocabulary richness that the author would expand upon throughout his life.

“Lujuria. Cuentos nefandos,” published in 1914, opens a new era of Cuban literature that combines an exacerbated and animalized sexuality with environments of moral degradation, also associated with drug use and, ultimately, with the underworld that emerges as a counterpoint to a false social morality, suffocating due to its rigidity and the demonization of pleasure.

In 1943 he published his work “Fábula de la vida apacible. Cuentos pantuflares” (Fable of a Peaceful Life. Slipper Tales), in which the descriptions of local customs occasionally subvert the narrative connection, with a style called precisely “pantuflar” by the author himself, alluding to the agility, calamus currente, with which the writer draws successive scenes and simultaneously captures the reader’s attention with the interesting narrative flow.

Some of his pieces, due to their brevity, can be considered precursors of the contemporary short story, unscrupulous in their treatment of the most burning topics of society at the time, naturalistic if one takes into account the lack of vocation to judge reality that some denote, although this is not a constant in his work.

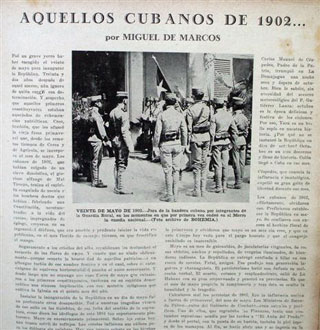

From a formal perspective, his work demonstrates an unusual command of the language and its varied registers, which contributed to his success as a journalist and the achievement of several awards. Among other publications to which he contributed are Tiempo, Prensa Libre, Diario de la Marina, La Nación, Heraldo de Cuba, El Mundo, Carteles, Avance, Bohemia, and Grafos, among others.

The theme of humor, with ironic overtones, is present in his work with a special Cuban touch; at the same time, he followed Jorge Mañach’s line of thought regarding “Indagación del Joteo,” rejecting this side of the coin of Cuban hilarity. His work constitutes an interesting legacy for national literature due to its treatment of themes and its questions about the essence of the Cuban.