4.3.5 The novelistic work of Jesús Masdeu Reyes (1887 – 1958)

The novel genre was cultivated with considerable success by Jesús Masdeu, whose career in this field included his first and major work, “La raza triste” (The Sad Race), 1924; “La gallega” (The Gallega), 1927; “Ambición” (Ambition), 1931; and also “El ensueño de los miseros” (The Dream of the Miserables), which remains unpublished. He also wrote the essay “Cuba, Tierra de esclavo” (Cuba, Land of Slavery), which shares its subject matter with the social material that gave shape to his novels.

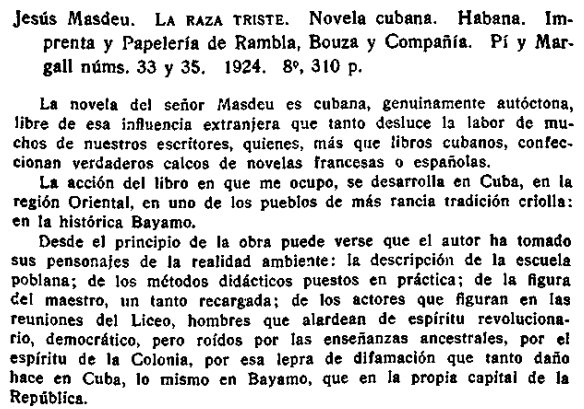

“La raza triste” (The Sad Race) is a heartfelt defense of the black race, set in the time between the dawn of the republic and the uprising of the black independents in 1912. The work shows that the end of slavery and some of the rights granted to blacks did not mean the end of racial discrimination, which was growing towards the highest levels of the social hierarchy.

The events take place in the city of Bayamo, whose society and its superficial values are described with verisimilitude. Of particular rebellious connotation is the episode of the delivery of an aristocratic white girl to the black character, protagonist, of Miguel Valdés, on a grave, undoubtedly approached with a certain romantic pathos of a serial imprint but valid in its desire to bring this subject to the fore, normally treated in reverse, due to a certain indulgence with which the extramarital relationships of white men and black women were perceived.

For his part, in “La Gallega,” he recreates the topic of peninsular immigration, although not entirely unusual, in the case of a woman and the material and moral ups and downs through which she is forced to abandon her hopes of economic and social advancement. The topic demonstrates the empathy the author established with members of the lowest social strata, subjected to harsh living conditions and under the aegis of a morality that was essentially alien to them.

In “Ambición,” he explicitly sets out to expose the vices that plagued neocolonial society, especially from a political and administrative perspective. The protagonist, Braulio Cañizo, aware that the prevailing situation required radical change, does not hesitate to adopt an upstart attitude to obtain political prerogatives and climb the economic ladder.

It seems entirely contradictory that the author dedicated this last narrative piece to Gerardo Machado, with the nuncupatory text that “he has fought them (the vices) at their deepest roots.” He even traveled to the United States in 1933 to interview the dictator after his overthrow. However, the rest of his journalistic career is noteworthy both for its content and for its literary flair, captured in “El Día,” “Heraldo de Cuba,” “El País,” “La Discusión,” “Pueblo,” “Excelsior,” and “Bohemia,” among others from the period.