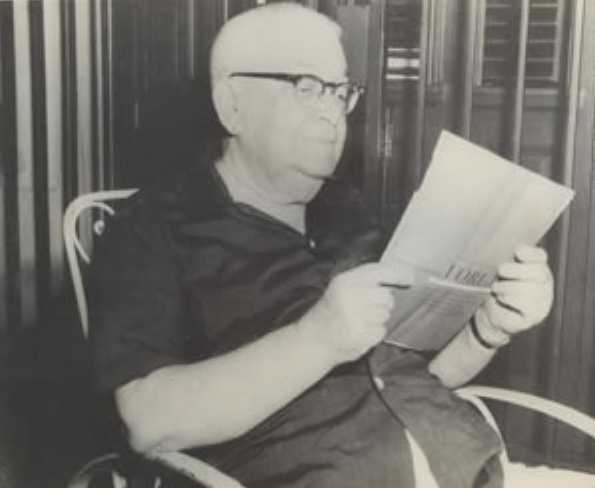

4.4.2.1 The first forays of Fernando Ortiz (1881 – 1969) into the field of essays and oratory

Fernando Ortiz spent most of his childhood in Menorca, Spain, returning to Cuba in 1895, where he published a short text on costumbrismo in the Menorcan dialect. He returned to Spain in 1899 to continue his law studies, and in Barcelona, he gave several lectures—published in a pamphlet in Havana in 1908—under the shared title “For Spanish Agony. Monographic Study of Menorcan Festivals.”

The studies surrounding this work allowed him to delve into the sources of Spanish culture, which he would later incorporate into his perspective on Hispanic heritage as part of the Cuban cultural “ajiaco.” In 1910, he published “The Reconquest of America,” subtitled “Reflections on Pan-Hispanism,” in which he established a continuity with his previous studies, although this time with a broader scope of research.

He also gave a short talk in Spain entitled “The Bad Life in Havana” as part of an exegetic commentary on a book titled “The Bad Life in Madrid.” This work demonstrates an interest that, although stemming from the field of criminology, would shift first toward the study of the Cuban underworld and then, with a broader scope, toward all the cultural interconnections that influence the behavior of Black social groups, increasingly expanding its scope to the island and with universal resonance.

In these initial investigations, purely scientific interest constituted the immediate leitmotif; however, patriotic sentiments would emerge as his research progressed and would contribute to shaping a broad and profound spectrum of ideas, of advanced ideological significance, relevant to the understanding and sense of Cuban nationality as an integrating whole.

According to Marcelo Pogolotti, “No sooner had he begun his research than the young researcher found himself faced with an intricate maze of paths called linguistics, mythology, history, ethnography, aesthetics, anthropology—the living anthropology in addition to physics—etc., etc. Thus, as he acquired knowledge of such generic subjects, he delved deeper into the virgin Afro-Cuban forest, glimpsing with amazement an immense wealth of legends, musical forms, dances, pantomimes, social systems, disturbing prehistoric evocations, and rites and liturgy of suggestive symbolism.”

This early period of Fernando Ortiz’s work was more one of meticulous observation and information gathering than of concrete results—although he always published some studies containing partial conclusions—his foray into the aforementioned disciplines was largely determined by the need he sensed to explore complementary realities and define certain concepts in order to delve deeper into the study of Cuban roots. However, his interests were so vast from a scientific standpoint that it is not valid to pigeonhole them thematically.