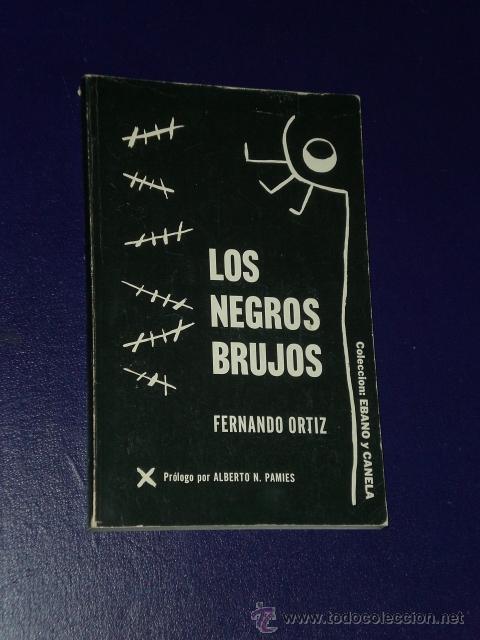

4.4.2.4 “The Black Witches”, 1906, by Fernando Ortiz (1881 – 1969)

The first edition of “Los negros brujos” (The Black Witches) was published in Madrid in 1906 and received rave reviews, including from César Lombroso, considered the precursor of positivist-influenced criminology. The primary purpose of this work is “criminal ethnology,” but it already reveals sociological concerns that go beyond the scope of crime and would determine the study of diverse cultural manifestations per se.

Although positivism imposes inevitable biases on research in the social sciences, at the time it had a refreshing epistemological character, and Ortiz does not strictly adhere to it; however, certain racist undertones, from a purported biological perspective, are evident in the text and affect the objectivity of some of its arguments.

In any case, the text constitutes a first blow to scientific racism, by shifting the behavioral differences between blacks and whites from the biological to the purely cultural, even though it considers the white race to be of “superior civilization.” However, it manages to imbue itself with the cultural fabric of Black Africans and base its analyses on their axiology rather than a purely European perspective on morality.

The author also manages to penetrate the maze of African religious beliefs and cults, which are somewhat heterogeneous, to establish comparisons and accurately point to a common foundation that somehow links all religions, including Catholicism. In this sense, he comes to understand that there was no such thing as “primitivism” or inferiority in religion, but rather diverse manifestations of a magical-thaumaturgical thinking inherent to humanity since its dawn.

Despite a certain biological bias and a discriminatory concept of civilization, in this work Fernando Ortiz paves the way for an understanding of the African and succeeds in understanding that there were no psychological differences between races. The very fact of his concern and attention to the Black theme gives him a relevant place in our culture, in the sense of a vindicator, from a high conception of science.

According to Miguel Barnet, “This work, published more than ninety years ago, reveals the lower strata of Cuban society that had never before been studied (…) It is a book surpassed by Fernando Ortiz, but it is his first solid work, where one could already glimpse the author’s capacity and the ambitious social spectrum he sought to encompass. This work, judged by the implacable generations that succeeded him, reinforces the figure of Ortiz and allows him to fully develop in the field of social sciences.”