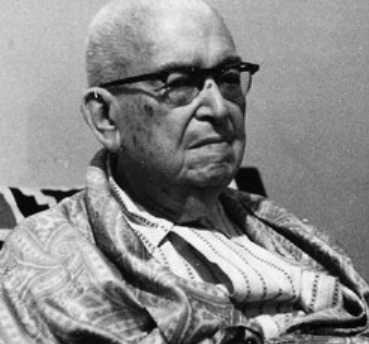

4.4.2.6 The political theme and anti-imperialism in the work of Fernando Ortiz (1881-1969)

Although Fernando Ortiz was above all a fighter in the realm of ideas, a bearer of a revolutionary spirit rooted more in culture than in clear ideological significance, he nonetheless assumed and expressed a political stance and commitment in the nation’s most difficult times. In this sense, he voluntarily exiled himself to the United States during the final stages of the Machado regime and expressed the right of all peoples to freedom.

Miguel Barnet describes his actions in the following terms: “A shaper of generations, he was a member of the Minorista Group, a stalwart of anti-imperialism; he founded and created institutions and magazines. He signed every document and appeal against imperialism and racial discrimination submitted to him.”

In his early days as a thinker, he did not yet foresee the evils of the republican political system and, like so many other intellectuals, placed his hopes in education and, fundamentally, culture as a means to the development of the country, primarily intellectually, but also economically, under the seal of bourgeois liberalism.

Many of his ideas on this subject are expressed in his 1919 pamphlet, “The Cuban Political Crisis, Its Causes and Remedies,” in which he attributes this sense of cultural deficit to underdevelopment, from a class dichotomy perspective. However, he would realize that culture—although essential for development—was not a panacea for so many neocolonial scourges, and he already points to “the economic predominance of foreign elements” as one of the underlying causes.

In 1927, he published “Economic Relations between the United States and Cuba,” followed by a series of works that demonstrate the maturing of the idea that Cuba should achieve its second independence. Along these lines, in 1931, he published “The Situation in Cuba,” “The Responsibilities of the United States in the Evils of Cuba,” and “Cuba Needs to Be Free Again and Will Truly Be So,” a programmatic expression of a principled position he would not abandon.

In 1934, he also published “A New Form of Government for Cuba. A Way to End the Series of Dictatorships,” where he outlined some ideas that would be better outlined in “Cuban Counterpoint of Tobacco and Sugar”: “Cuba will not be truly independent without freeing itself from that twisted serpent of the colonial economy that feeds on its fields, but strangles its people and coils around the palm of our republican shield, turning it into a foreign dollar sign.”

Some allusions he made in “A Cuban Fight Against the Demons,” published in 1959, suggest a pre-existing sympathy for the Revolution, although he remained somewhat on the sidelines, perhaps due to his affiliation with bourgeois liberalism or perhaps because he was more inclined to offer tacit support, devoid of bombast, needing to witness the unfolding of events, which was skewed by his death in 1969.