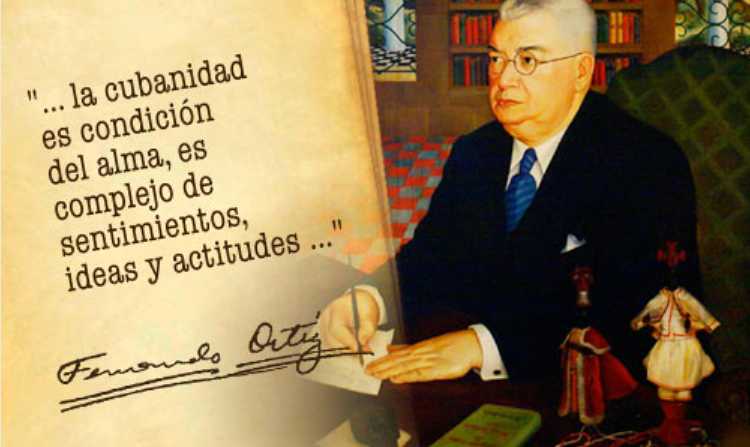

4.4.2.13 Cubanness, Cubanness and its roots in the work of Fernando Ortiz (1881 – 1969)

Although Fernando Ortiz’s work is often associated exclusively with Black and African themes, the truth is that his studies of this nature ultimately served to unravel the roots of Cuban identity in a synchronic and diachronic sense. Proof of this are his studies on Hispanic culture, Native American culture, and even the theme of migration as one of the phenomena that shape our identity.

The aspects and pieces that directly address the Black theme, integrated into our future as a people, have already been addressed, so we will refer to other bibliographic pieces that explore various roots and manifestations of Cubanness, not especially Black ones.

In 1910 he published the article “Cuban Folklor” (Cuban Folklor), which already showed a broad outlook that could not be reduced to African heritage, but rather explored a multiple past from a racial and cultural perspective, and was also interested in the present, in the coexistence and integration of customs and symbols from diverse sources. He had not yet coined the term “transculturation” for this purpose.

He was also interested in the historical development of the nation and the independence struggles, a subject which included biographical notes on 19th century heroes and intellectuals, such as José Antonio Saco (José Antonio Saco and his Cuban ideas, 1929) as well as his contribution “Italy’s sympathies for the Cuban mambises, documents for the history of Cuban independence”, published in Marseille in 1905, which was also a diplomatic tribute to the ties between the two nations.

In 1913 he published in Paris “Entre cubanos (Psicología tropical)” in which he compiled articles on a certain thematic diversity but tending to establish the autochthony of the Cuban above even the roots that he dedicated himself to studying with so much effort.

In 1922, he published “History of Indo-Cuban Archaeology,” in which he compiled the discoveries of this discipline and interpreted them in light of his positivist theoretical concepts. Geographically, it was located in the Caribbean and sought to pinpoint the origins of the island’s first inhabitants, as well as the customs and habits that somehow remained in the people’s ancestral memory. He elevated these studies to a qualitatively higher level with “The Four Indian Cultures of Cuba,” published in 1943.

Two texts, the first of them a speech, which are key to understanding his perspective on the circumstances and situations that had contributed to the formation of national identity are “Cuban Decadence, a speech of renewing propaganda, from 1924 and “The Factors of Cubanness”, already in 1940, in which his sense of an independent Cuba is also present, through the abolition of the Platt Amendment and, already in the second, the adoption of a revolutionary program, in addition to his well-known simile of ajiaco to define our culture.

In general, the Cuban aspect is not restricted to one or another of Ortiz’s works, but is present as the heartbeat and destiny of his scientific and cultural inquiries. Although he did not join the trappings of the Revolution nor was he given to triumphalist enthusiasm, he did share its essence, equalizing all Cubans in search of a better future for the country. Juan Marinello affirmed that the scholar had been the “third discoverer” of Cuba, although his work remains to be discovered.