4.4.4 The cultivation of the essay genre by José Antonio Ramos (1885 – 1946)

What most defines José Antonio Ramos’s intellectual personality is his persistent analytical vocation, which determined that throughout his life he transformed his own postulates and occasionally changed his perspective in the study of social and cultural realities, not only in Cuba but also in the global context and even in the United States, which has caused some confusion among exegetes of his works.

The two works he published during this period are titled “Entréactos” (Intermissions), from 1913, and “Manual del perfecto fulanista” (Manual of the Perfect Fulanist), from 1916. Given its importance, the latter will be addressed in a separate section.

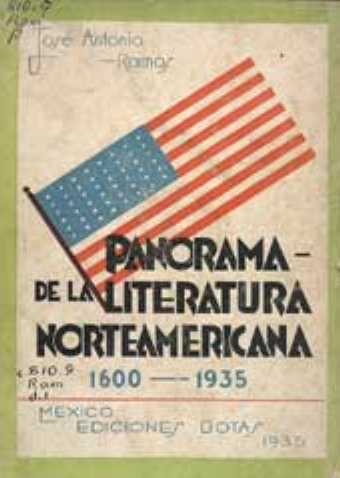

He was a great connoisseur of North American culture and the political foundations of its actions. He even published the text “Panorama of North American Literature,” which reveals a certain admiration for the country, its writers and its history, but at the same time investigating the hegemonic germs that had already manifested themselves and the resulting dangers for Cuba and Latin America. He also inherited the Martí perspective with an objectivity that focuses above all on the fight for Cuban nationality from the intellectual sphere.

In both works cited above, he speaks out against the foreignizing tendency that undermined society, the dazzlement of the American way of life, and the foreign in general; in this regard, his writing career maintained an attitude of openness toward other cultural universes without abandoning his roots, and he strived toward constantly elevating them to higher levels.

In his writings, he addresses the country’s fundamental problems, in his view, both political and ethnic. Regarding the latter, he had already announced his disregard for the concept of “white,” as the future of a race, instead speaking of “Cuban,” following Martí’s line of thought when he expressed that Cuban was more than white, more than black, more than mulatto… in his well-known thesis of Cubanness and struggle.

His political and cultural views evolved as he deepened his long-held analytical attitude. His initial ideas regarding an intellectual elite occupying the country’s political leadership gave way to a new perspective on the working class and the need for their struggle, with a spontaneous approach to Marxism, though not to its profound philosophical core, and without abandoning the positivism of its certain pragmatic roots.

He also worked in the consular field and, in his later years, ventured into the field of library science. His work also includes plays and theater criticism. His diverse texts have been published in “Cuba Contemporánea,” “La Noche,” “Social,” “Revista de la Habana,” “Cuba Contemporánea,” “El Fígaro,” “Cervantes,” “Revista de Avance,” “El Siglo,” “Noticias de Hoy,” “Revista Bimestre Cubana,” “Información,” “El Comercio,” “Letras,” “Gazette del Caribe,” “El Sol,” “El Mundo,” and other publications. He occasionally used the pseudonyms “El Capitán Araña” and “Pancho Moreira.”