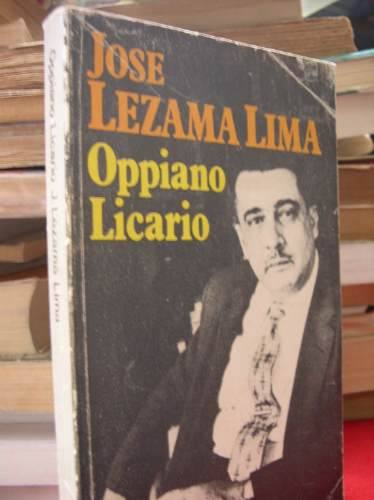

4.1.2.2.10 The unfinished text of “Oppiano Licario”, 1977, written by José Lezama Lima (1910 – 1976)

Undoubtedly, “Oppiano Licario,” the last text written by José Lezama Lima and published posthumously in 1977, lacks exegetical studies of the breadth and scope carried out on “Paradiso.” However, some clues have already been revealed. For example, it has been proven that the text was indeed left unfinished, based on a review of the manuscript of “Outline for Hell.”

“Oppiano Licario”; although it possesses an independent coherence—within the limits imposed by its status as an unfinished text—is also unquestionably the continuation of Paradiso, not only because of the preexistence of the character who ultimately gave the work its title, but also because of the spatial and temporal coordinates, the atmosphere, and other extra-literary reasons drawn from Lezam’s correspondence.

However, there is also debate as to whether the novel’s unfinished nature was also an invention of Lezama’s, something foreseen in the interstices of the narrative, within the imaginative universe he articulates throughout the text. In this regard, Enrico Mario Santí, who researched the text and context of “Oppiano Licario,” stated:

“Oppiano Licario’s text not only discusses the phenomenon of fragmentation, of death, but also anticipates its own interruption, its own fragmentation, and refutes it in advance, thus correcting any truncated reading that interrupts or fragments the totality that the text claims.”

As in “Paradiso,” “Oppiano Licario” reveals, in a holistic sense, literary processes from various schools, some of which have emphasized the contributions of the avant-garde. Although Lezama criticized the vagueness of this movement in itself, it undoubtedly represented an opening toward new expressive modes that would achieve their own identity and shape the panorama that nourished Lezama’s poetry and, later, his novels, not immanent but certainly a leading avant-garde.

In the text, which begins with an episode of costumbrismo, the reference to a specific period in the nation’s history is decipherable, including the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista and the ensuing liberation struggles. Likewise, some point to the influence of the revolutionary period, more pronounced than in Paradiso, thereby affirming a writing style in which the vernacular and the eminently national reach a new level of meaning, in which reality and mythological fiction point to a “refoundation” of the nation.