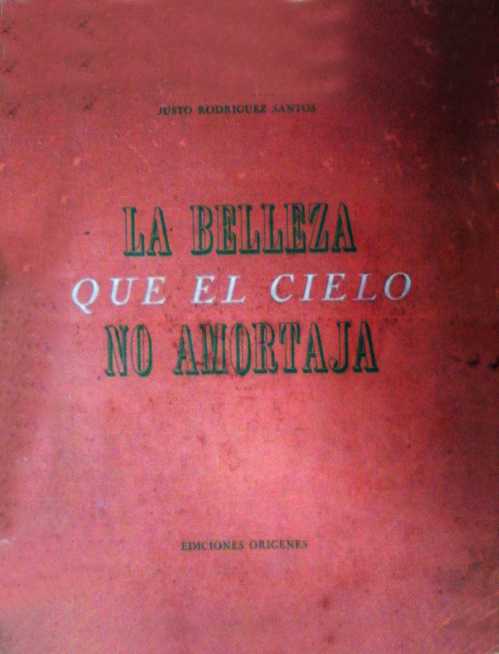

4.1.2.5.2 The poetry collection “The beauty that the sky does not shroud”, by Justo Rodríguez Santos

“The Beauty That Heaven Does Not Shroud,” by Justo Rodríguez Santos, was published by Ediciones Orígenes in 1950. The collection of poems is composed exclusively of sonnets, distributed in the sections of Portico, The Beauty That Heaven Does Not Shroud, Night and Stalking, Inheritance of Memory, Tomb in the Dream, Turbid Deity, Country of Absence, The River, Coast of Love, Pale Interlude, and Voice in the Darkness.

The collection of poems begins with the following sonnet, which already demonstrates the excellent workmanship that generally characterized his poetic works of this kind. In addition to the perfect aesthetic finish, a communicative intention is evident, the need to establish a poetic communion with readers, beyond human contingencies:

“Regain your joy, cross the dream,

ask the scorpion, not the dawn;

interrogates the murdered star,

walk through that garden without flowers or owners;

the embers of the nocturnal effort continue

and you will find, at a serious crossroads,

my word crowned with thorns,

my voice like a cross of crackling wood.

Bring your heart closer with a firm hand,

so that he may drink from the dark river

of this convulsive and daily dying;

and you will listen, in your empty corner,

the music of a superhuman song

throwing the light of my name!”

The eponymous section, “The Beauty That Heaven Does Not Shroud,” is composed of eight sonnets whose ultimate meaning remains unclear, beyond the lyrical resonance of some verses and the iterations of death and beauty. The text is surrounded by a veiled mystery that evokes a multitude of interpretations but also a certain conceptual emptiness.

Sonnet number four, whose final verse gives its title to the section and also to the collection—a process used on other occasions by Justo Rodríguez, as part of a circular writing that closes in on itself—expresses the battle between death and beauty, where the devouring nature of the former, the inexorability of Cronus, ultimately constitutes the only thing that endures. Its final stanzas are transcribed:

“In vain does his vigil mobilize;

Death, inexorably, surpasses him

and time enslaves him to its rigors.

And towards the neutral peace he sees how it goes down

the profile that devours the ashes,

the beauty that heaven does not shroud.”

Many of the texts in the collection express a muted interrogation of reality, perhaps of death, which is echoed in a broad spectrum of feelings. Although there is no explicit reference to God, the divine is intuited as the ultimate answer, a teleological explanation of the events and psychic manifestations through which the poet travels.

Not entirely similar to the rest of the collection, the second sonnet of Pale Interlude, entitled “Defend your hope” constitutes the most explicit text in terms of message, in which beatitude, beauty, hope, are offered as a necessary path to abolish the shadows that life brings, in a certain way contrasting with the preeminence of death in other poems:

“Defend your hope, your message,

which is the voice of love that flows towards the eternal.

Its clarity gathers and replaces

the deaf darkness of your language.

May hope illuminate your landscape,

the land that oblivion destroys you;

stop the soul that flees among thistles;

Let hope be your lodging.

Anticipate your strength to fear.

Build your prosperity within yourself.

Beatitude opposes your sadness.

Regain your confidence in your eyes

to look at the unparalleled Beauty.

Defend your message, your Hope!