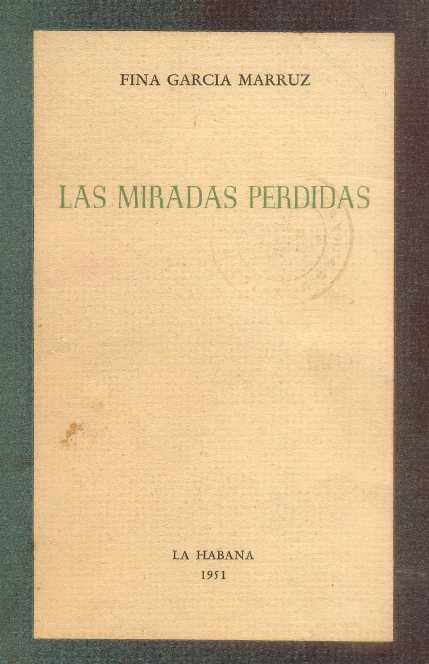

4.1.2.10.2 “Lost glances”, a collection of poems published by Fina García Marruz (1923 – ) in 1951

“Lost Looks” is Fina García Marruz’s first transcendent work, revealing the quality of her poetry as an emanation of self, an outlet toward the exterior, and not a mere play on words. Some critics, including Cintio Vitier himself, had pointed out a certain formal sloppiness as part of a conception of poetry as a true expression through which the soul evolves, with a higher purpose than itself. However, here, a greater aesthetic refinement is already evident, nonetheless unrelated to the purpose of imbuing beauty.

One of the poems in which we appreciate the greatest lyrical display, although secondary with respect to the inner vision that it tries to transmit, of a deep religiosity and which is in it the primordial source of poetry, is undoubtedly “Transfiguration of Jesus on the Mount”, previously published as a single, in 1947. Its conception of the exterior is also reflected in these verses, associated with the surrender of Jesus, comparable in a certain way to the authentic writing act of the poet:

“…On the mountain his body cannot resist Him who never

He knew how to think of nothing that could not share his chest

or both hands;

Oh, we could hardly understand it. He has

turned completely external like light;

like the light He has refused intimacy and has become

completely thrown out of himself;

but not as one who flees but as one who returns,

He who keeps his part like he who divides a loaf of bread;

Like the light He remembers the source that flows in the

hidden and occupies the exact extension of its name;…”

This piece constitutes one of the greatest exponents of Catholicism transposed lyrically, associated with a fertile emotionality that does not stop at the liturgical but seeks to recover the meaning of the covenant, this time in the substance of poetry.

Although the previous verses written by Fina Garcia Marruz already present notable aesthetic successes, bearers of a worthy poetic, nourished by the warmth of reading the classics but with a clear experiential breath, here she truly achieves her creative singularity and already shows the religious guideline of her poetry, as well as her clear identification with her native island and from there her desire to capture the national identity, as elusive as the very concept of the poetic.

The text also includes pieces dedicated to Rosalía de Castro and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. In this sense, although a particular piece cannot be cited, the Cuban aspect constitutes a hidden tremor that runs through the entire collection, concomitant with the religious topic and the theme of death, all in a refined style that had already achieved sufficient discoveries to figure in the history of national lyric poetry.