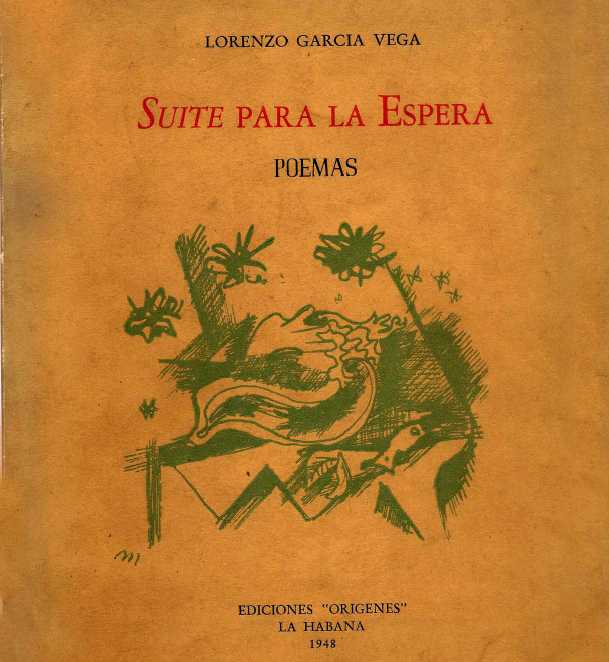

4.1.2.11.2 The poetry collection “Suite for Waiting”, 1948, by Lorenzo García Vega

The collection of poems “Suite for Waiting” was published under the Orígenes imprint in 1948. It outlines many of the qualities that would characterize Lorenzo García Vega’s later poetic work. From a formal perspective, it combines poetic prose and free verse, fractured into a variety of images. One of the younger Orígenes poets, his debut work received Lezama’s salutation:

“The wait for the Suite is central and tense. There’s a word that seems key to this book: tension. Verse after verse, a poetic verb ardently turned upon its labyrinth, now little concerned with threads and doors, secures the circle of the poem in its center and proportion. If the ancients knew visual drinks, in this book by LGV, a flavor appears, divined and pursued by the eyes, a fugitive grouping assured in a visual gallop.”

Lezama transfers to his words the synesthesia in the apprehension of reality that is appreciated in many of Lorenzo García Vega’s poems, a unitary perception that the poet does not separate into sensory parcels, nor does he essentially distinguish from his accumulated sensory experience, since he lays down the containing dam of reason to let flow a lyricism that responds to other laws, more psychic than purely poetic.

In “Ode,” we see a dreamlike panorama of pure poetic fertility, where the bard seeks to soar back into his slumber. Despite the hermeticism of a distinctive symbolism, woven into the unconscious and whose spheres of meaning are not contained within the old conventions of words, the sense of a conception of poetry itself is discernible in the final verses:

“The Ode is a breeze, a flake, the rush of being in its emptiness

Empty? Snowing, a hole in silence, in a flash,

the neighbor accuses you of your gestures

The Ode wanted to be the foot of the riders who once

they overcame the lightness of the dream!”

For its part, the poetic text that gives the collection its title, which is transcribed below, suddenly captures what was poetic novelty for the author: the “decapitated swans” seem to refer to a modernist revolt from which the poet wants to escape at all costs; the tuned sounds of Pan’s flute are replaced by the hoarse, throat-splitting piccolos:

“RAPIDS”, in cotton dolphins, laughter. Tropes of the

afternoon melt frozen mirrors, west.

The “why,” as an idiotic malice. As irony.

of the snow. Sailboats rise, retreat, hatch fish from

crystal: ballet of decapitated swans.

I toast with the branches of my forehead, smoke of marble;

with my old clown, without, his cheesy ruby, his rabbit sphere.

and quietly I cut the throats of hoarse piccolos. Thus the God

“Bread will die in the textbook.”

The volume contains topical allusions to Cuban culture, such as in the text “Nocturno para Matanzas,” which does not feature the compositional techniques of surrealism but rather a lyricism based on evocation, anchored in ancient perceptions but grounded in reality. Beach, bridge, villages, taverns, tram… these are references that help to piece together the memory of a lost city, from a poetic perspective.

In some texts, dialogue occupies a prominent place, sometimes with the potential reader and other times within a fragmented self. Overall, the text displays a distinct aesthetic, also imbued with Origenist quests, but beyond them, the poet persists in a self-inquiry that is not contemplative, but rather like a whirligig that emits images and finds itself within its framework. The collection of poems deserves a more in-depth analysis that unravels the meaning of its unusual associations.