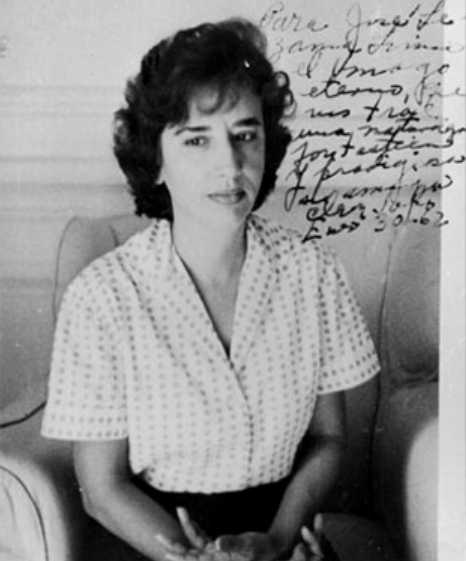

4.1.2.12.1 Cleva Solís (1926 – 1997), his work in Orígenes and until the end of the republican era

Cleva Solís’s literary forays, published in the magazine “Orígenes,” date back to 1955 and 1956. The first is a poem entitled “La mancha” (The Stain), and the second is a lyrical narrative entitled “Las escrituras” (The Writings), both of which contain Solís’s lyricism, which begins with the senses but unfolds through difficult intellectual twists and turns.

In one of its readings, the aforementioned poem constitutes a questioning of divine order—or disorder. Creation is seen not only from its paradisiacal perspective but also from the mud and misery—a word repeated in the text—of both nature and humanity. Here, Solís’s intellect rises above the dictates of faith, where the biblical myth of Job is, in a sense, latent.

Other biblical allusions do appear interwoven throughout the text to illustrate the dual nature of creation, both miracle and pain, two poles within the lyrical discourse. In this sense, “Elisha’s bones” have not lost their capacity to procreate miracles, coexisting in some way with “that dung,” a way that perhaps, from a very irreverent perspective, refers to creation. The final verses are transcribed:

“But the dance grows, and the misery grows.

The light is as remote as the pergolas and gardens.

The sea breaks against the walls

and its paradisiacal delights flourish.

From time to time he enters into God’s mess

and seems oblivious to his presence,

when he cleans and sets his crowns,

and its fleeting birds on the temples.

The music spins its plot lightly,

and its frozen flowers

full of faded triumphs,

They rise elongated and thin

like brittle crystals

or fleeting reeds.

Butterflies jump out of that dung

and the snake charmer

raises with the misery of his flute,

“the quails and the trees.”

For its part, the lyrical text of “The Scriptures” from its very title has a certain biblical connotation, reinforced by the allusion to Sodom and Gomorrah and by the fluid disorder of words – Babel of myth refounded? – However, the hermeticism of the text and a certain estrangement are evident, from a perspective that comes from the alienation of the subject, an improper and timeless look.

In 1996, Cleva Solís published “Vigilia,” which had a profound impact on its cultural landscape; even Vitier considered it the revelation of the year. The book is influenced by Origenist aesthetics, but its detachment from circumstances takes on an air of alienation, a clear product of the social situation of its time, which does not detract from its value as a literary work. Cleva Solís, in a sense, concludes the cycle of her concomitance with “Orígenes” to delve into the very densities of her existence and, above all, of her thinking.