2.3 Historical overview of the theatre in the 16th century

Sixteenth-century theater in the Old Continent had similarities and differences across the nations that comprised it, in terms of scenery, actors, costumes, and the spaces where performances were held, among other aspects. The forms and rules developed during this period shaped much of European theater for several centuries.

During this century, the new style known as the Renaissance, which emerged in 15th-century Italy, spread throughout the rest of Europe. Theater also experienced significant development in Spain and Latin America; writers began experimenting with theater again, giving rise to new theatrical forms. These include puppets, operas, and ballets.

Theatrical architecture emerged during the Italian Renaissance, and from the early 16th century onward, ostentatious theater buildings began to be built, reserved for grand performances. Art became increasingly the preserve of the upper social classes, as the forms and language presented by scholarly comedy and pastoral drama were inaccessible to the general public, as they were beyond the reach of the masses.

In Italy, the commedia dell’arte, a popular theatrical form, emerged. Angelo Beolco began performing short plays with a group of friends. These plays, written in the Paduan dialect, depicted the lives of peasants, and featured fixed characters throughout. In them, Beolco mocked, to a certain extent, the peasants, while also highlighting the values of that social class. The performances by this young man and his companions took place during Carnival. Gradually, troupes of actors were formed, inspired by Beolco’s work; the admission fees were shared among all members and women were allowed to appear.

Some time later, this new theatrical form, with its popular characteristics, became established in Italy. Its distinctive features included the priority given to the actor, the use of masks and fixed characters, the use of dialects, and the inclusion of slapstick elements. Commedia dell’arte at this time was understood as professional theater, which was simply that which allowed its members to dedicate themselves to it and earn a living from it. Its characteristics were consolidated between 1570 and 1580.

Commedia dell’arte lacked a literary basis, so at first, authors took the plot from a known play, just the story line of that play, that is, the action, to which they added other actions and forgot about the written text, which was improvised by the actors. Later, its definitive form was established, consisting of a script that outlined a plot rich in action and left the text to the spontaneous improvisation of the actors. Over time, a few fixed texts were collected for each character, which the actor learned by heart and interspersed throughout the different plays. Improvisation circumvented censorship, due to the lack of a play script, making each play seem unique in every performance.

A commedia dell’arte actor was required to have a great imagination and a flair for words, as pure improvisation filled most of the performance. He also had to be able to perform acrobatics, sing, dance, and play musical instruments. Each actor had an emploi, or fixed character, that is, the same character they played for their entire acting career. Each character had their own costume and mask, hence the commedia dell’arte is also known as the comedy of masks. Among the best-known masks were the zanni, foolish but sane and cunning peasant types.

The use of dialect allowed for greater communication with the audience, conveying numerous proverbs, jokes, popular sayings, and expressions of language. It also allowed actors to say things that were beyond the understanding of censorship officials. Plays usually had three acts.

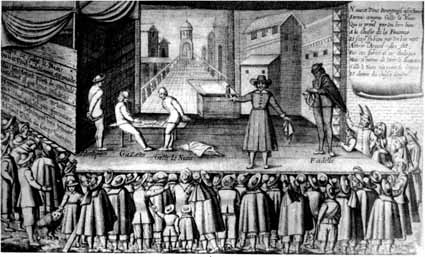

At first, when comedians traveled from town to town, the stage for these plays was an improvised stage with a backdrop representing the facades of houses, separated by streets. Their humor was generally crude and even rude, but it gained considerable fame, and they were soon invited to court and began traveling abroad, achieving success in countries such as Austria, Poland, Spain, Russia, England, and, above all, France.

This spread and the very characteristics of the genre led to its decline. Despite its limitations, its success endured for two centuries or more. Among the contributions of the commedia dell’arte, we find that it emphasized the importance of the actor and the action on stage; it laid the foundation for the subsequent development of professional theater, among others.

Meanwhile, during this period, one of the most successful plays was the cynical farce The Mandrake (1524), written by Machiavelli. Another play that has survived and is currently being performed is La Celestina, by the Spanish playwright Fernando de Rojas. The latter had 24 acts, unusual for its time, and featured a constant change of scenery.

At the beginning of this decade, morality plays were very popular. They attested to the Church’s intention to instruct the public about the Christian attitude toward death. The plot was based on the comparison between Good and Evil in the souls of men. The play always ended with the redemption of its protagonists.

In the mid-16th century, the Protestant Reformation put an end to religious theater; in its place came a new and dynamic secular theater. This new form of theater was based on themes about humanity’s struggles and adversity, a shift toward more secular themes and more temporal concerns, and the return of the comic and the grotesque. Professional actors also began to appear in productions.

The great popularity of miracle plays continued into this period, when the Baroque orientation of the autos predominated. Unknown authors incorporated various scenes into the biblical narratives (on which the miracle plays were based), created in the form of short realistic comedies, alluding to investigations and problems experienced at the time of the performance. One play that gained wide popularity in England was the Second Shepherd’s Play, part of the Wakefield cycle.

Sacramental plays display a more complex organization than the dramatic genres that preceded them and are considered the predominant expression of Baroque religious theater. Among the most significant writers of these plays are Lope de Rueda, Juan de Timoneda, and Alonso de la Vega.

The highest peak of 16th-century religious theater is evident in the work of Gil Vicente. At the end of the century, the Church prohibited the performance of many autos; this was recorded in 1559 when a document was published in Toledo, which also called on the authors to respect and fear religious doctrine.

Theater was the literary genre that took the longest to reach its full development in the Spanish Golden Age. The lyrical works written during the first decades of the 16th century by the founder of Portuguese classical theater, the poet and playwright Gil Vicente, are among the earliest theatrical works.

The so-called Jácaras, also part of Spanish theater, which featured music, song, and dance, were very popular during this period and throughout the 7th century. Among their practitioners were Luis Quiñones de Benavente, Jerónimo de Cáncer, Calderón de la Barca, Antonio de Solís, Francisco de Avellaneda, and Juan de Matos.

Throughout the reign of Henry VIII, the court masque flourished in England, specifically in the year 1512. It became the most significant theatrical form during the reign of James I, being perfected and incorporating brilliant lyricism thanks to the English playwright and poet Ben Jonson.

In Elizabethan England (1558-1603), theater acquired unprecedented popularity, filling a vast cultural void and the public’s thirst for entertainment. Medieval theater forms—miracles, mysteries, and morality plays—were overrepresented. During the Renaissance, the secular works of new English authors, which sought to portray reality, eventually displaced religious theater.

From the beginning, the theater in England had a strong enemy in the Puritans. They viewed the theater as a conglomeration of religious shamelessness and paganism. For this reason, theater was banned within the limits of London, as a result of Puritan influence. In 1576, the first English theater was built on the other side of the River Thames by the carpenter James Burbage. Other theaters were later established, such as The Globe, The Fortune, and The Rose; until, over time, there were simultaneous performances in eleven theaters in London.

The Elizabethan theatrical period was unique in its time, as if we compare theatrical activity in England with that of other countries, we can see that it was superior. For example, in Madrid there were only two or three venues operating, and in Paris only one.

Actors performed in inns or lodging houses before the first theater in England, where a platform was improvised at one end of the courtyard. Later, theater architecture followed the same pattern as those in these venues. There were two types of theaters: public (with affordable prices and accessible to everyone) and private (expensive and exclusive).

The latter were indoors, and performances were offered during the day. They were characterized, like those offered at court, by luxurious costumes and scenery. Among them was the Blackfriars, whose repertoire consisted of mythological or musical plays, staged by troupes of child actors. Plays became very popular in England, and increasingly sophisticated theaters began to be built.

All English actors were men. Plays, divided into five acts, could have between twenty and thirty characters, and the company of actors never exceeded twelve or fourteen; therefore, the author was careful not to have two characters played by the same actor in the same scene. The entire play was performed in two hours, and at most, in three. Almost all of them, or at least the most important authors, were also actors.

We find that several authors collaborated on a single work, a common occurrence. John Lyly, George Peele, Thomas Nash, Thomas Kyd, Ben Jonson, and William Shakespeare are some of the most important English authors.

Shakespeare (1554-1616), today one of the most widely read, translated, and published writers in the world, was the most important author of his time. He created hundreds of characters and wrote thirty-seven plays, including comedies, tragedies, historical dramas, and ancient dramas. He transformed the drama of his time, combining the beauty of language with dramatic construction and also reflecting the history of his country in his dramatic chronicles.

In Spain, we could find theater companies made up of a single actor traveling from town to town, or groups of two, three, or four actors. There was also a larger category, made up of up to thirty members, who had a repertoire of fifty comedies. These companies were also made up of female actresses. Comedy groups rented the space to offer their performances.

Theatrical buildings began to be built starting in 1575. These continued to be called corrales (the backyards of tenement houses or inns where performances were held). The shows were almost always held outdoors; however, a tarp was sometimes used to shade the courtyard. The actors’ costumes were contemporary attire, regardless of the period of the play. 16th-century Spanish theater actors were poor and marginalized people; they had to possess certain skills, such as singing, fencing, dancing, and an excellent memory.

Plays were divided into three acts, between which an interlude (a short humorous piece) or a jácara (a sung poetic composition) was performed. Music was an important component of Spanish theater. Fernando de Rojas, author of La Celestina (1499), is considered the pioneer of Spanish theater.

Other significant Spanish authors were Lope de Rueda, Miguel de Cervantes y Saavedra, Tirso de Molina, and Lope de Vega. Lope de Rueda is considered the father of Spanish comedy. He was the most accomplished and exuberant playwright in the theater; he wrote around 1,500 plays, including comedies of intrigue, love, and historical dramas; and more than 300 sacramental plays and praise plays. Tirso de Molina created works of profound moral and Christian significance, with secular themes. Among Lope de Vega’s contributions, we find that he shaped a truly national theatrical expression, fused comic and serious elements in his plays, and consolidated the character of the Gracioso, or figure of wit.

Puppets were also abundant in 19th-century Spain. Puppet groups of some standing were allowed to offer their performances in corrals (barnyards) when the acting troupes were adjourned. These performances criticized customs and established norms in a vulgar and sometimes rude manner, so it can be said that they followed the tradition of the commedia dell’arte. Because of these characteristics, they had to abandon the public scene and began performing in private homes, in front of family groups. Puppets in Spain then went from being a simple household entertainment to becoming a spectacle aimed at children.

Opera emerged in the late 16th century, with elaborate stage displays and intermezzi as its precursors, combined with ongoing attempts to recreate classical productions. Early classical theater had a limited audience, but opera nevertheless became very popular.

Bibliography: Rine Leal. A Brief History of Cuban Theater.